Limitation of State aid to companies which have a durable link with the local economy can be compatible with the internal market.

Introduction

By prohibiting barriers to free movement and establishment in the internal market, the EU seeks to make the choice of location of a company largely irrelevant. All companies should be treated the same regardless of where they happen to be. Member States, however, enjoy considerable discretion in how they regulate their economies, as long as their rules comply with EU law. This variation of national rules does influence the choice of location of companies even when the rules do not overtly discriminate against foreign companies.

A perennial question in the field of State aid is what kind of links the beneficiaries of State aid should have with the economy of the aid-granting Member State. It makes sense that a country should make aid available only to those companies which are active in its own territory and can contribute to correcting the particular market failure that is targeted by State aid. Crude exclusion of companies established abroad, licensed abroad or owned by foreign shareholders is not allowed. But there is a big difference between outright exclusion and the minimum necessary local presence.

In February 2021, the General Court upheld Commission decisions authorising State aid schemes that were limited to airlines licensed in the aid granting Member States on the grounds that that was a more effective means of combating the effects of covid-19. In April and May 2021, the General Court upheld Commission decisions authorising individual aid measures which by definition excluded all competitors even though they were also affected by covid-19.

This article reviews the judgment of 19 May 2021 in case T‑628/20, Ryanair v European Commission, by which the General Court also upheld restrictions in terms of the place of establishment and the principal place of business.[1] This is a worrying development because the restrictions appeared to go beyond what was necessary to remedy the serious economic disturbance caused by covid-19.

Ryanair applied for annulment of Commission Decision SA.57659 of July 2020 authorising a Spanish recapitalisation fund in the context of the Temporary Framework. The recapitalisation fund aimed to provide liquidity to strategic but viable enterprises which were experiencing temporary difficulties due to the impact of covid-19.

It is important to note at the outset that Member States has wide discretion to determine the specific objectives of their State aid measures, as long as they fall in the categories of exemption defined in the Treaty. This is even more so in the case of Article 107(3)(b) which allows aid to remedy as serious economic disturbance. There are many ways to remedy such a disturbance. Recent research on the economic impact of pandemics identifies loss of jobs in the short term and loss of human capital in the long term.[2] As will be seen later, Spain chose to support undertakings whose bankruptcy could cause significant job losses. This is a legitimate policy aim. It could have also chosen to remedy the impact of the pandemic on those undertakings which were more instrumental in the preservation or development of the set of labour skills that would be necessary for the economy of the future [e.g. linked to the “green” or “digital” economy].

The point is that there can be many different measures which are appropriate to remedy the various impacts of the economic disturbance caused by the pandemic. However, once Member States choose the impact or aspect that they wish to remedy, the instruments they use to achieve the policy objective must be necessary and proportional. I will argue that limiting the eligible beneficiaries to those with a place of establishment and the principal place of business in Spain was neither necessary, nor proportional.

The main criteria of eligibility as defined by the Spanish authorities were:

- Establishment (seat) and principal place of business in Spain.

- Systemic or strategic importance to the economy.

- Exposed to risk of ceasing operations or having serious difficulties remaining in business.

- High negative impact on the economy from cessation of activities.

- Possible viability in the medium to long-term.

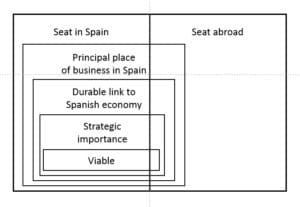

We will see later on that the General Court agreed with the Commission and Spain that for a company to be of strategic significance to the Spanish economy, it needed to have a stable presence and durable connection to the economy and also, in order to contribute to recovery from covid-19, it would have to have good prospects for return to viability. Therefore, for a company to be formally eligible for aid and to be able to contribute to the achievement of the objective of the aid measure it had to satisfy the following conditions: seat in Spain, principal place of business in Spain, a durable link with the local economy, strategic importance and a good chance to become viable in the future. These conditions can be visualised in a venn diagram below, which also shows that logically a company established abroad [i.e. with its seat abroad] could also satisfy all of the those conditions. Neither Spain, nor the General Court excluded the possibility that a foreign company could have its principal place of business in Spain, a durable link with the local economy and a strategic position there.

Conditions of eligibility

Because I make extensive comments on the judgment, my views are written in italics to avoid confusion between the judgment and the comments.

Infringement of the principle of non-discrimination?

Ryanair argued that the Commission Decision infringed the principle of non-discrimination, because the Spanish measure discriminated against undertakings that were not established in Spain and did not have their principal place of business in Spain.

In its analysis of Ryanair’s argument, the General Court, first, recalled the fundamental principle of exemption that “(25) the procedure under Article 108 TFEU must never produce a result which is contrary to the specific provisions of the Treaty. Therefore, the Commission cannot declare State aid, certain conditions of which contravene other provisions of the Treaty, to be compatible with the internal market. Similarly, State aid, certain conditions of which contravene the general principles of EU law, such as the principle of equal treatment, cannot be declared by the Commission to be compatible with the internal market”.

“(26) In the present case, it is clear that one of the eligibility criteria for the aid scheme at issue, namely that the beneficiaries must be established in Spain and have their principal places of business in the territory of that Member State, results in different treatment.”

“(27) If, as the applicant claims, that difference in treatment can be equated with discrimination, it must be examined whether it is justified by a legitimate objective and whether it is necessary, appropriate and proportionate for achieving that objective. Similarly, in so far as the applicant refers to the first paragraph of Article 18 TFEU, it must be pointed out that, according to that provision, any discrimination on grounds of nationality within the scope of application of the Treaties is prohibited ‘without prejudice to any special provisions contained therein’. Therefore, it is important to ascertain whether that difference in treatment is permitted under Article 107(3)(b) TFEU, which is the legal basis for the contested decision. That examination requires, first, that the objective of the aid scheme at issue satisfies the requirements of that provision and, second, that the conditions for granting the aid do not go beyond what is necessary to achieve that objective.”

The Court found the first condition to be satisfied. “(29) Since the existence of both a serious disturbance in the Spanish economy as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and of the significant adverse effects of the latter on the Spanish economy, have been established to the requisite legal standard in the contested decision, the objective of the aid scheme at issue satisfies the conditions laid down in Article 107(3)(b) TFEU.”

“(30) The criterion of the strategic and systemic importance of the beneficiaries of the aid properly reflects the objective of the aid scheme at issue, namely to remedy a serious disturbance in the Spanish economy within the meaning of Article 107(3)(b) TFEU.”

With respect to the second condition [appropriateness, necessity and proportionality], the Court observed that

“(32) as regards the appropriateness and necessity of the aid scheme at issue, it should be noted that, in the present case, the scheme was adopted pursuant, inter alia, to Section 3.11 of the Temporary Framework entitled ‘Recapitalisation Measures’”. Therefore, the measure addressed the effects of covid-19.

With respect to the appropriateness of the requirement for eligible undertakings to be established in Spain and to have their principal place of business there, the Court made the following observations.

“(35) In view of the nature of the recapitalisation measures at issue, it is legitimate for the Member State concerned to seek to ensure that the undertakings likely to benefit from that scheme have a stable presence on its territory and a durable link with its economy. The authorities of that Member State must be able to monitor, on a continuous and effective basis, the manner in which aid is used, compliance with the governance clauses and all other measures imposed to limit distortions of competition. They must also be able to organise and monitor the subsequent orderly withdrawal of the Spanish State from the capital of those undertakings. To that end, the Member State concerned must have the power to intervene, if necessary, in order to ensure compliance with the conditions and commitments surrounding the grant of the public financial support in question.”

Three comments are in order in relation to the reasoning in paragraph 35 of the judgment. First, the Court implicitly admits that the decisive elements are not the seat and principal place of business but stable and durable presence. Second, the Court ignores to ask whether the Spanish authorities would have been prevented from monitoring effectively foreign companies whose Spanish subsidiaries would receive capital. And, third, the Court also ignores that an aid grantor can always make the aid conditional on acceptance by the aid recipients of reporting and auditing obligations. The aid grantor can always give itself the “power to intervene”. In fact, State aid rules do require Member States to impose such obligations on aid recipients so as to ensure that aid is not misused [i.e. it is actually used for the purpose for which it is granted]. The point is not that Spain should not have required close monitoring of the aid recipients, but that it could have also monitored closely foreign companies whose seat of establishment was in other Member States.

“(36) The eligibility criterion relating to the beneficiaries of the aid being established in Spain and having their principal places of business in the territory of that Member State thus reflects the need for the Member State concerned to ensure a certain stability of their presence and their durable links to the Spanish economy. That criterion requires not only that the beneficiary should have its seat in Spain, but also that its principal places of business be located in that territory, which demonstrates precisely that the aid scheme at issue is intended to support undertakings which are genuinely and enduringly linked to the Spanish economy, which is consistent with the objective of the scheme, which is to remedy the serious disturbance in that economy.”

The Court implicitly recognises that the criterion concerning the seat and principal place of business is a proxy for a genuine and enduring link with the local economy. It does not, however, demonstrate that all companies with a seat in Spain and carrying out most of their business there have an enduring link, nor does it prove that foreign companies cannot have a genuine and enduring link. This, of course, raises the question how the presence of such link can be proven otherwise. I think it can be left to aid applicants to show that they have a substantial presence for a sufficiently long period of time. After all, the ultimate objective of the aid measure in question is to support strategic companies. A foreign company whose Spanish operations are of strategic importance would have been able to demonstrate that.

“(37) By contrast, the existence of such stable and durable links to the Spanish economy is, in principle, less likely in the case of both mere service providers, whose provision of services may, by definition, cease at very short notice, if not immediately, and in the case of undertakings which are established in Spain but which have their principal places of business outside the territory of that State, so that any public financial support intended to support their activities is less likely to contribute to remedying the serious disturbance in the economy of that Member State.”

The use of the words “less likely” undermines the reasoning of the Court. Even if that is an empirically correct finding, it does not prove that a seat in Spain is a necessary condition for stable and durable links with the Spanish economy. The Court does not consider the possibility of a company established abroad but which has its principal place of business in Spain. It also ignores that the aid grantor can always make the aid conditional on maintenance of the aided operations for a certain period of time [see, for example, the requirement in the GBER and the regional aid guidelines that the aided assets of foreign companies which invest in assisted areas are to be kept there for a minimum of five years in the case of large enterprises or three years in the case of SMEs].

“(39) It is clear that the aid scheme at issue is granted only to undertakings regarded as being of systemic or strategic importance for the Spanish economy. By targeting the aid scheme at issue in this way, the Kingdom of Spain has chosen to support only those undertakings which play a key role in its economy, since their difficulties would seriously affect the general state of the Spanish economy because of their systemic and strategic importance. Accordingly, undertakings which are not regarded as systemic or strategic for the Spanish economy cannot claim the benefit of the aid scheme at issue, even though they are established in Spain and have their principal places of business in the territory of that Member State.”

The last sentence above begs the question that if establishment in Spain was not a relevant element, then why was it an eligibility condition and why it was ok for companies established elsewhere to be excluded?

“(40) Several other eligibility criteria also reflect the need for the Spanish State to ensure that there is a durable link, that is to say, in the medium and long term, between the beneficiaries of the aid and its economy. Thus, the criterion relating to the systemic and strategic importance of the beneficiaries refers in particular to ‘their role in achieving the medium-term objectives of ecological transition, digitalisation, increased productivity and human capital’. Another eligibility criterion requires beneficiaries to establish their medium and long-term viability by presenting a viability plan indicating how the undertaking concerned could overcome the COVID-19 crisis and describing the planned use of State aid (paragraph 10(d) of the contested decision). In addition, the undertakings concerned must submit a planned schedule of reimbursement of the nominal investment of the State and measures that would be adopted to ensure that that schedule will be met (paragraph 10(e) of the contested decision). Those criteria thus reflect in a concrete manner the need, first, for the beneficiary in question to be enduringly integrated into the Spanish economy and to continue to be so in the medium and long term, so that it can meet the abovementioned development objectives and, second, for the Spanish authorities to be able to monitor compliance with and implementation of their commitments.”

I agree with the explanation of the Court above that what ultimately mattered was the impact that the aid recipient could have on the Spanish economy and that the aid recipient had to prove that it had a viable plan so that the injection of capital could add value to the economy. But by the same token, the restrictions concerning the seat and place of business were neither necessary, nor sufficient for that purpose. And, the fact that the aid recipients had to commit to a viable plan and to reimburse the capital they received, undermined the argument that the Spanish authorities have to limit the aid to Spanish companies in order to ensure compliance with the aid measure.

“(43) Thus, by limiting the benefit of the aid solely to undertakings of systemic or strategic importance for the Spanish economy, established in Spain and which have their principal places of business in its territory, because of the stable and reciprocal links between them and its economy, the aid scheme at issue is both appropriate and necessary to attain the objective of remedying the serious disturbance in the economy of that Member State.”

The statement in paragraph 43 does not follow logically from the preceding analysis, for example, in paragraph 37, of the Court itself. In fact, immediately below, the Court, in the context of its analysis of the proportionality of the aid, admitted that there was no one-to-one relationship between establishment in Spain and strategic importance.

Then the Court went on to examine the proportionality of the aid. It began by conceding that “(45) while it cannot be ruled out that an undertaking which is not established in Spain and does not have its principal places of business in that Member State may nevertheless be of systemic or strategic importance for the Spanish economy in certain specific circumstances, it should be recalled that the grant of public funds under Article 107(3)(b) TFEU presupposes that the aid provided by the Member State concerned, even though it is in serious difficulty, is capable of remedying the disturbances in its economy, which presupposes that the situation of the undertakings likely to enable the economy to recover is taken into account as a whole and that the criterion of a stable and durable link with the economy of that State is fully relevant.”

“(46) First, the need for a stable and durable link between the beneficiaries of the aid and the Spanish economy, which underlies the aid scheme at issue, would be lacking or at least weakened if the Kingdom of Spain had adopted another criterion allowing the eligibility of undertakings operating in Spain as mere service providers, such as the applicant, since the provision of services may, by definition, cease at very short notice, if not immediately, as is pointed out in paragraph 36 above. Thus, the Kingdom of Spain has no guarantee that the contribution to its economy from undertakings which are not established and which do not have their principal places of business in its territory would be maintained after the crisis, assuming that they were granted the benefit of the recapitalisation measures.”

Once more we see that the Court jumps from the need for a durable link, which is indeed necessary for the objective of the measure, to the proxy of establishment and principal place of business, which is not necessary. Also, it does not consider that Spain would oblige anyway aid recipients to submit plans and would grant aid only to those whose plans could demonstrate their impact on the economy.

“(47) The fact that the applicant is the largest airline in Spain, holding approximately 20% of the market in that Member State, or that its exit from that market would lead to social hardship, does not mean that the Commission committed an error of assessment in finding that the aid scheme at issue was compatible with the internal market. That argument is based on the applicant’s specific situation in the market for passenger air transport in Spain, whereas the aid scheme at issue is intended to support the whole Spanish economy, without distinction as to the economic sector concerned, so that the Kingdom of Spain has taken account of the overall state of its economy and the prospects for economic development in the medium and long term, and not of the specific situation of any one undertaking.”

Two comments are in order here. First, the Court earlier referred to the specific situation of “service providers” as an example of companies with tenuous links with the Spanish economy [paragraphs 37 & 46]. But now it dismisses the specific situation of Ryanair. Second, even when the Commission assesses a scheme it has to examine whether criteria of general application are suitable or necessary for the achievement of the objectives of the aid measure in question.

“(48) Therefore, by laying down conditions for granting the benefit of a general and multisectoral aid scheme, the Member State in question could legitimately rely on eligibility criteria designed to identify undertakings which are both systemically or strategically important for its economy and have durable and stable links to it.

Indeed Member States are free to limit their aid measures to undertakings which are systemically or strategically important.

“(49) As regards the alternative aid scheme advocated by the applicant, based on an eligibility criterion relating to the market shares of the undertakings concerned, it should be recalled that, according to the case-law, it is not for the Commission to make a decision in the abstract on every alternative measure conceivable since, although the Member State concerned must set out in detail the reasons for adopting the aid scheme at issue, in particular in relation to the eligibility criteria used, it is not required to prove, positively, that no other conceivable measure, which by definition would be hypothetical, could better achieve the intended objective.”

Although, as the Court states, the Commission may not demand proof that all alternative measures have been considered, nevertheless, the Commission has to assess the suitability of the eligibility criteria for the measure, as designed by the Member State concerned, and the policy objective, as defined by that Member State. This is not an exercise in hypothetical scenarios. It is an analysis of the logical consistency of the eligibility criteria and the objective of the aid. As argued earlier, it is doubtful that the eligibility criteria were all suitable.

More broadly, the Spanish recapitalisation scheme shows the pitfalls of using multiple eligibility criteria. Spain could achieve the same objectives simply by limiting the aid to important undertakings with a viable plan and which accepted to maintain operations over a certain period of time. This could have excluded Ryanair objectively and regardless of Ryanair’s market share, if Ryanair did not employ enough persons in Spain. In this way there would be no need to speculate on how long aid recipients would commit to serving the Spanish market.

Infringement of the principles of freedom to provide services and freedom of establishment

Next, Ryanair argued that the Spanish measures created obstacles to the freedom to provide services and to establish commercial presence in Spain.

The General Court, first, recalled that “(57) the provisions of the FEU Treaty concerning freedom of establishment are aimed at ensuring that foreign nationals and companies are treated in the host Member State in the same way as nationals of that State”. “(58) The freedom to provide services precludes the application of any national legislation which has the effect of making the provision of services between Member States more difficult than the provision of services purely within one Member State, irrespective of whether there is discrimination on the grounds of nationality or residence”.

“(61) Although it is true that, because of the definition of the scope of the aid scheme at issue, the applicant is deprived of access to recapitalisation measures granted by the Kingdom of Spain, it has not established how that exclusion is such as to deter it from establishing itself in Spain or from providing services to and from Spain. In particular, the applicant fails to identify the elements of fact or law which cause the aid scheme at issue to produce restrictive effects that go beyond those which trigger the prohibition in Article 107(1) TFEU, but which, as was found in the context of the first two parts of the first plea, are nevertheless necessary and proportionate to remedy the serious disturbance in the Spanish economy caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, in accordance with the requirements of Article 107(3)(b) TFEU.”

The Court makes two important statements in paragraph 61. First, State aid has an intrinsic or inherent discriminatory effect [because it is selective] but if this effect is compatible with the internal market [on the basis of Article 107(2) or (3)] then, it does not fall within the scope of the prohibition of obstacles to free movement in the internal market. Second, it reiterates its earlier conclusion that the intrinsic discriminatory effect of the Spanish scheme did not go beyond the minimum acceptable extent because it was necessary and proportionate. However, as argued earlier, the eligibility criteria were more restrictive than necessary in view of the objective of the aid measure.

Weighing the beneficial effects of the aid against its adverse effects

Ryanair also contended that the Commission failed to weigh the effects of the aid measure.

The General Court rejected that contention on the grounds that Article 107(3)(b) does not require a balancing exercise.

“(66) It follows from the wording of [Article 107(3)(b)] that its authors considered that it was in the interests of the European Union as a whole that one or other of its Member States be able to overcome a major or possibly even an existential crisis which could only have serious consequences for the economy of all or some of the other Member States and therefore for the European Union as a whole. That textual interpretation of the wording of Article 107(3)(b) TFEU is confirmed by comparing it to Article 107(3)(c) TFEU concerning ‘aid to facilitate the development of certain economic activities or of certain economic areas, where such aid does not adversely affect trading conditions to an extent contrary to the common interest’, in so far as the wording of the latter provision contains a condition relating to proof that there is no effect on trading conditions to an extent that is contrary to the common interest, which is not found in Article 107(3)(b) TFEU”.

“(67) Thus, in so far as the conditions laid down in Article 107(3)(b) TFEU are fulfilled, that is to say, […] the aid measures adopted to remedy that disturbance are, first, necessary for that purpose and, second, appropriate and proportionate, those measures are presumed to be adopted in the interests of the European Union, so that that provision does not require the Commission to weigh the beneficial effects of the aid against its adverse effects on trading conditions and the maintenance of undistorted competition, contrary to what is laid down in Article 107(3)(c) TFEU. In other words, such a balancing exercise would have no raison d’être in the context of Article 107(3)(b) TFEU, as its result is presumed to be positive. Indeed, the fact that a Member State manages to remedy a serious disturbance in its economy can only benefit the European Union in general and the internal market in particular.”

In a sense, the requirement that compatible aid must be proportional also functions as a sort of balancing of the positives and negative effects of the aid because disproportional aid causes a distortion that goes beyond the minimum that is necessary for the achievement of the objectives of the aid.

The Court also found that the Temporary Framework did not require a balancing exercise “(69) because such an obligation does not appear in the Temporary Framework.”

The General Court also rejected several other pleas put forth by Ryanair and went on to dismiss the appeal in its entirety.

[1] The full text of the judgment can be accessed at:

[2] See M-A. Barbara, C. Le Gall & A. Moutel, The Economic Effects of Epidemics, Tresor-Economics (French Ministry of Economy and Finance) no. 279, March 2021, and the references cited therein. It can be accessed at https://www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Articles/2021/03/16/the-economic-effects-of-epidemics