The Annual Competition Report is a useful document, but it should provide more information on the results of the ex post evaluations and ex post monitoring.

Update on Temporary Framework:

Number of approved and published COVID-19 measures, as of 10 July 2020: 202*

Legal basis: Article 107(2)(b): 20; Article 107(3)(b): 171; Article 107(3)(c): 17

Six Member States have implemented 11 or more COVID-19 measures each: Belgium, Denmark, France, Hungary, Italy & Poland.

– Average number of measures per Member State: 7.2

– Median number of measures per Member State: 8

– Mode number of measures per Member State: 5

* Excludes amendments to previously notified measures

Introduction

What is the purpose of the annual report of a public institution? It shows how the institution has carried out its tasks. The annual report is primarily an accountability instrument. It explains how the institution has implemented the policy for which it is responsible and how it intends to remedy any shortcomings.

Annual reports have also two other functions. They lay out the future plans of the institution and educate those on whom public policy imposes obligations or to whom it provides rights.

The Commission published on 9 July 2020 the Annual Competition Report for 2019.[1] It explains quite thoroughly how the Commission enforces competition rules and its future plans as several antitrust and State aid rules are under revision.

The 2019 Report also has a substantial educational value. It publishes useful statistics and highlights important cases, decisions and court judgments.

However, the Commission is not transparent enough on two issues: its assessment of the ex post evaluations of measures with large budgets and the results of its ex post monitoring of the application of approved and GBER-based measures. This article explains below why this is a problem and why it makes compliance more difficult for Member States.

In this connection I should also mention that the Commission has not done enough to educate all stakeholders – not just the State aid coordinators in Member States – on the correct interpretation of the provisions of the GBER. The guidance on the GBER that is published is from July 2015 and March 2016. Since then the Commission has provided much more explanation to Member States without making it publicly available. Given that EU courts have repeatedly stated that aid beneficiaries need to check that the aid they receive is granted legally and that assurances from national authorities to that effect do not create legitimate expectations, the Commission, as a public institution, has an obligation to enable companies to assess for themselves whether aid is granted to them legally. They also need to be aware of the information that the Commission provides to Member States on the interpretation of the GBER and of other State aid rules. Correct understanding of the law should not be a secret or privilege. Dissemination of this information would not create any extra administrative burden on the Commission. Simple publication on its website should suffice.

Although the Annual Report covers all areas of competition policy, this article reviews only the sections that refer to State aid. Two documents are covered here. The first is the Annual Report itself. The second is a Staff Working Paper that accompanies the Report.

Part 1: Annual Report

The Report, at only 28 pages, is relatively short. With respect to State aid, it gives prominence to the “fitness check” of all the main State aid rules and presents the timeline of public consultations and the process of revision of those rules.

It should be recalled that last week the Commission prolonged the GBER and de minimis Regulation to the end of 2023 and the main Guidelines to the end of 2021 so that it can have more time for a thorough fitness check.

The Report also highlights the Commission’s push for State aid that supports the EU’s climate targets, environmental protection, energy efficiency and energy security through capacity mechanisms. It also highlights the approval of State aid for an R&D project in battery technology that was classified as an “important project of common European interest”.

A chapter of the Report is devoted to State aid in tax measures. With regard to advance tax rulings, the Report refers to the endorsement by the General Court of the Commission’s use of the “arm’s length principle” in the cases concerning Fiat and Starbucks. The Report reaffirms the commitment of the Commission to fight State aid that is granted by means of “aggressive tax planning”.

Another chapter is devoted to State aid to financial institutions. Interestingly, all three cases mentioned in that chapter – NordLB (Germany), CEC Bank (Romania) and the Hellenic Asset Protection Scheme (Greece) – were free of State aid because public funds and guarantees were granted on market terms. In fact, in 2019, the Commission also found that two other cases were free of State aid: Hypobank Steiermark (Austria) and BancoPosta of Poste Italiane (Italy).

The Report also refers to State aid in agreements between airports and airlines, in the maritime sector and to providers of postal services.

Part 2: Staff Working Document

The Staff Working Document [SWD] is three times longer than the Annual Report and provides more details.[2] Like the Report itself, the SWD covers all areas of competition policy. On State aid it has individual chapters on the following topics:

- “Uptake of the State aid Modernisation”

- “State aid Modernisation continues”

- “Monitoring, recovery, evaluation and cooperation with national courts”

- “Significant judgments by the European Union Courts in the State aid area”

In addition, it cites important cases and decisions on a sector by sector basis [e.g. energy, manufacturing, taxation, transport, etc.].

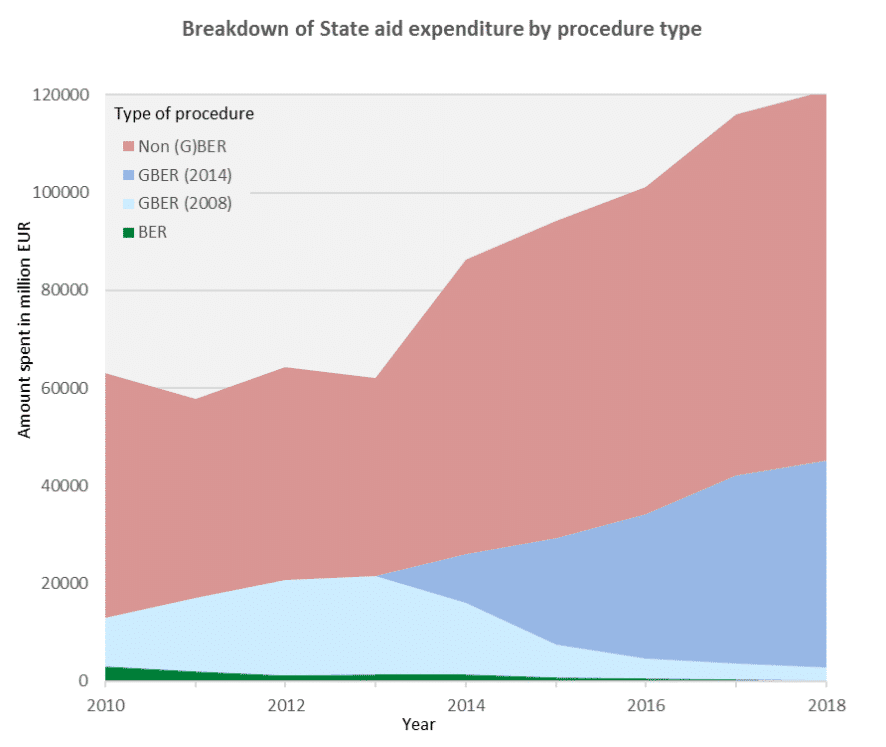

With respect to the “uptake of the State aid modernisation”, the SWD finds that Member States have been using the GBER for the vast majority of State aid measures. “Approximately 89% of all measures with reported expenditure (that is to say not only new measures), fell under the block exemption in 2018.” However, in terms of volume of aid, less than half of all aid in 2018 – which amounted to EUR 45 billion – was granted on the basis of the GBER. This is also shown in Graph 1 below.

Graph 1

[Source: European Commission]

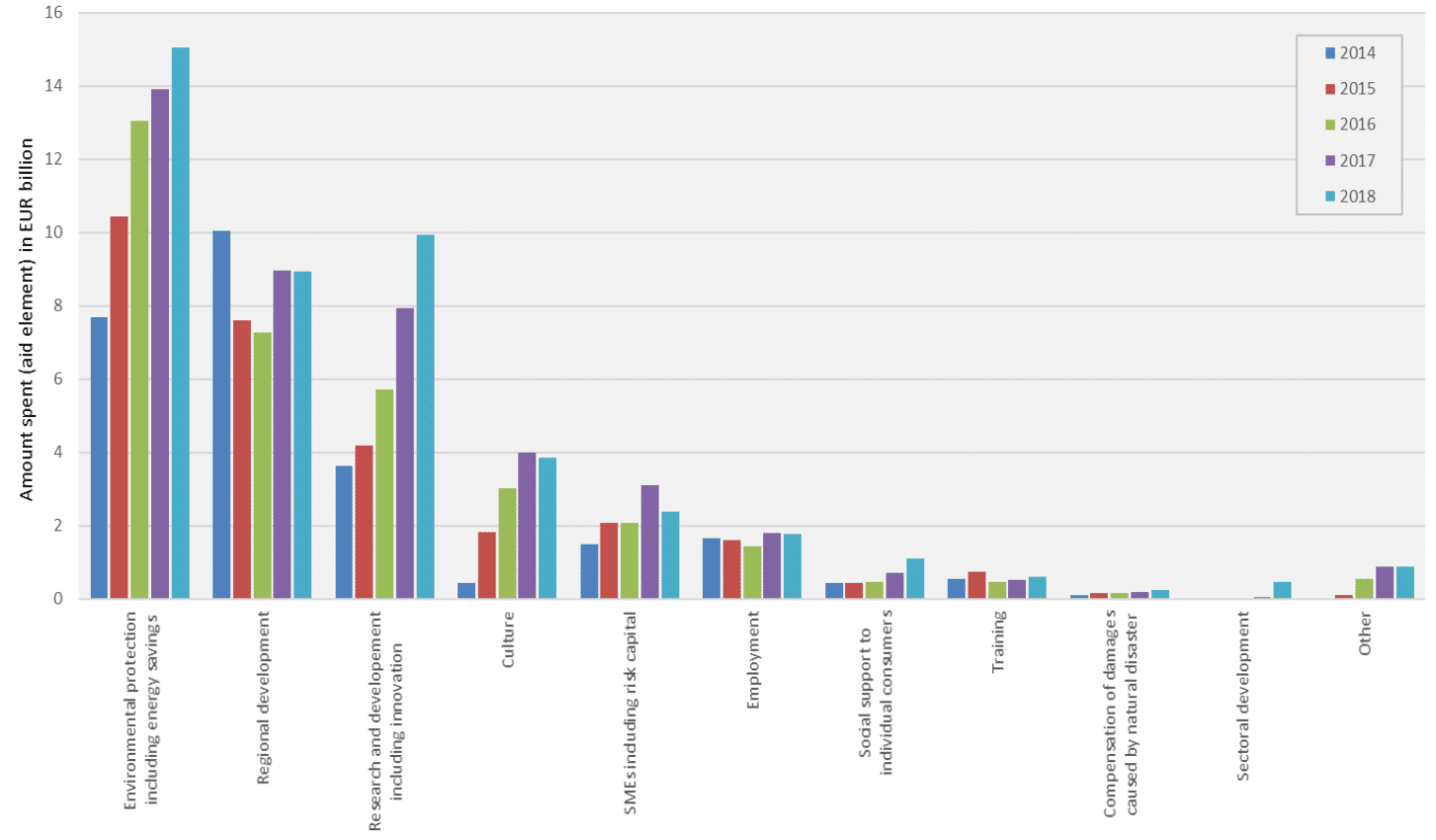

The use of the GBER also varies significantly across sectors as well as policy objectives. Graph 2 below shows that most aid granted on the basis of the GBER went to environmental protection and energy efficiency. However, in relative terms, proportionately more aid is granted on the basis of the GBER for other policy objectives such as culture and heritage conservation, RDI, and training.

Graph 2

[Source: European Commission]

Transparency register

As is well known, an innovation of the 2014 GBER was the requirement for publication of all individual awards of aid exceeding EUR 500,000. The SWD indicates that by the end of 2019, the register operated by the Commission recorded more than 73,000 individual awards to 33,000 different beneficiaries. What is perhaps less well known is that only 25 Member States (and Iceland) have joined the Commission’s register.

Ex post evaluation

Another innovation of the 2014 GBER was the mandatory ex post evaluation of State aid measures with annual budgets exceeding EUR 150 million. Ex post evaluation is also required of schemes with novel features outside the GBER even if their budgets are smaller. By the end of 2019, the Commission had approved evaluation plans for 45 schemes. Three other schemes were awaiting approval.

Only 15 Member States have implemented measures which are subject to ex post evaluation [Austria, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK]. Most evaluation plans concerned regional aid, RDI, risk finance, energy and broadband schemes. The SWD states that “by the end of 2019, the Member States had delivered to the Commission 16 interim and four final evaluation reports, which were assessed by the Commission services and considered to be of average to good quality.” Although the Commission has not published the results of its own assessment of the quality of the evaluation plans, it has become known that no plan was found to be free of faults.

Member States are required to publish the evaluation reports. Ex post evaluation is a new tool and Member States have much to learn from each other’s experience, good or bad. Since, however, it is not known which Member States have completed and/or submitted reports, it is very difficult to gain access to them. The Commission can provide a much needed service to Member States if it becomes more transparent itself about the contents, methodology and mistakes of the ex post evaluations that have been completed so far. As we are approaching the end of this period of State aid rules and as the new rules will soon be adopted, it will be important for Member States to have a much better understanding of good and not so good practices on ex post evaluation and of the effectiveness of the various State aid instruments. This should enable them to make a more informed input to the discussions on the shape of the new rules and to improve the design of their own State aid measures in the future.

– Ad –

European State Aid Law (EStAL) provides you quarterly with a review of around 100 pages, containing articles, case studies, jurisdiction of both European and national courts as well as communications from the European Commission. EStAL covers all areas pertaining to EU State aid and subsidies, among others:

✓ The evolution of the concept of State aid;

✓ State aid Modernization;

✓ Services of General Economic Interest (SGEI);

✓ General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER);

✓ Judicial review of Commission Decisions;

✓ Economic assessment and evaluation;

✓ Enforcement at national level;

✓ Sectoral aid and guidelines.

Ex post monitoring

The purpose of ex post monitoring is to find out whether Member States apply correctly aid measures approved by the Commission and measures based on the GBER. The SWD indicates that in 2019 the Commission carried out about 50 ex post monitoring checks in 19 Member States.

The SWD does not reveal the number and type of irregularities identified by the Commission. Yet is has become known that irregularities have been found in about 40% of the measures examined by the Commission. Some of the errors are certainly innocuous. But some others may be more serious and can impact on the compatibility of State aid with the internal market.

This is another area where the Commission should be more transparent and help Member States to learn from each other’s experience. The Commission does not have to embarrass any Member State. It can simply anonymise the data it collects and publish them without any indication of their national origin.

Recovery of incompatible State aid

In 2019, the Commission ordered the recovery of incompatible aid in four cases. But by the end of 2019 there were still 42 pending recovery cases.

The amount of aid recovered in 2019 reached EUR 37.1 billion. The outstanding amount pending recovery was EUR 5.5 billion. Of this amount, about EUR 2.9 billion was made of claims registered in insolvency proceedings!

Important judgments in 2019

The SWD provides a list and brief explanations of important judgments in 2019. It categorises the judgments according to their relevance to State aid concepts and procedures. Most of them have already been reviewed here.

Advantage

Fiat and Starbucks: In both cases, the General Court stated that, “where national tax law does not make a distinction between integrated undertakings and stand-alone undertakings for the purposes of their liability to corporate income tax, that law is intended to tax the profit arising from the economic activity of such an integrated undertaking as though it had arisen from transactions carried out at market prices.” “Therefore, to assess whether a fiscal measure granted to an integrated undertaking constitutes an advantage, the Commission may compare the fiscal burden of such integrated undertaking with the fiscal burden of an undertaking carrying out its activities under market conditions. The arm’s length principle is a tool for making that determination, since it is a ‘benchmark’ for establishing whether an integrated company is receiving an advantage within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU. In order to apply the arm’s length principle, the Commission can rely on the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, which, although non-binding, reflect the international consensus achieved with regard to transfer pricing and have therefore a real practical significance in the interpretation of issues relating to transfer pricing. Furthermore, in order for an advantage to be proved, the errors identified in the calculation of a transfer price must go beyond inaccuracies inherent in the application of a method designed to obtain a reliable approximation of a market-based outcome.”

Micula: “The General Court found that the arbitral award did not compensate the applicants for the withdrawal of unlawful or incompatible State aid, but constituted a mere compensation for damages, which does not constitute an advantage for the purposes of Article 107(1) TFEU.”

Fútbol Club Barcelona: “The General Court rejected the Commission’s assessment of the advantage by stating that the examination of the nominal preferential tax rate cannot be dissociated from that of the other components of the tax regime of non-profit organisations.”

Real Madrid: “The General Court upheld the Commission’s findings on the need for Municipality of Madrid, acting as a private investor, to obtain independent legal advice before concluding an agreement with Real Madrid and that the value of the compensation agreed under that agreement was above market terms. However, the General Court found that the Commission was wrong to have limited its analysis of that agreement only to whether the compensation granted by the Municipality of Madrid to Real Madrid was on market terms. The Commission should have inquired whether the value of the plots of land Real Madrid received as a payment in kind for part of the compensation granted as a result of the 2011 agreement were in fact worth the value that Real Madrid had accepted they were worth.”

Mytilinaios: “The Court of Justice found the MEOP not to be applicable in this case because the measure consisted in an order for interim measures by a national court, which cannot be assimilated to an action of a market economy operator.”

Arriva Italia: “The Court of Justice concluded that the MEOP was not applicable. The Court of Justice observed that the Italian state did not carry out an ex-ante assessment of the profitability of the measure in point (the transfer of the shareholding in the capital of FSE). Moreover, the Court of Justice noted that: (a) it was apparent from the national legislation that such transfer of shareholding sought, in particular, to ensure the continuity of employment and transport services provided by FSE; (b) such transfer also pursued the objective of maintaining public sector shareholding in the capital of FSE. However, such considerations are not taken into account by a private investor.”

Selectivity

Fiat: “The General Court confirmed that the contested tax ruling related exclusively to Fiat and that therefore the Commission was correct in considering that ruling as an individual measure, and not as a measure granted on the basis of a scheme, as Luxembourg argued. In this regard, the General Court recalled that the assessment of the selectivity requirement differs depending on whether the measure in question is envisaged as a general scheme of aid or as individual aid. In the latter case, as established by the MOL case law, the identification of the economic advantage is, in principle, sufficient to support the presumption that the individual measure is selective. Based on this presumption, the General Court concluded that, since the Commission had established that the contested tax ruling granted an advantage, that advantage should in principle be considered selective, without the need to apply the three-step test.”

Turnover taxes [Poland and Hungary]: “The General Court found that these taxes were not selective because small and large undertakings were not in a comparable factual and legal situation in light of the redistributive purpose of the progressive turnover taxes. Therefore, the tax was not considered as discriminatory.”

Economic activity

Aanbestedingskalender: “The Court of Justice held that if an economic activity carried out by a public entity cannot be separated from other activities connected with the exercise of public powers, the activities of that entity as a whole must be regarded as being connected with the exercise of public powers.”

French ports: “The General Court confirmed that the ports carry out an economic activity, in addition to their public power activities. Assessing whether these economic activities could be considered ancillary to the non-economic ones, the General Court took the view that there is no threshold below which all the activities of an entity would be considered non-economic if the economic ones represent a minority. If the economic activity of a given entity is separable from the exercise of public power, that entity must be classified as an undertaking for this part of its activities.”

State resources and imputability

Germany v Commission [EEG 2012]: “The Court of Justice held that the General Court was wrong to find that the funds generated by the EEG surcharge constituted State resources. On the one hand, the EEG surcharge cannot be assimilated to a levy, on the other hand, the General Court failed to establish that the state held a power of disposal over the funds generated by the EEG surcharge or even that it exercised public control over the Transmission Systems Operators responsible for managing those funds.”

Achema: “The Court of Justice distinguished between a system financed by a mandatory charge and administered by an entity directly or indirectly controlled by the state, which involves State resources, and a system of mere price regulation where private operators must finance a purchase obligation on their own resources.”

FVE Holýšov: “The General Court confirmed that it is sufficient to establish the presence of a mandatory charge (the levy at stake had a compulsory nature) to establish the existence of State resources.”

Banca Tercas: “The General Court considered that the Commission has to have sufficient evidence to prove that measures taken by private entities were taken under the actual influence or control of the State.”

Recovery

Eesti Pagar: “The Court of Justice concluded that any national authority having granted unlawful State aid is under an obligation to recover that aid. It also recognized, in case of recovery of unlawful aid, the need of the principle of effectiveness to be respected, even if interest is to be calculated based on national law.”

Arriva Italia: “The Court of Justice stated that it is for the national courts to draw all the necessary inferences from failure to notify State aid, in accordance with domestic law, with regard both to the validity of the acts giving effect to the aid and the recovery of financial support granted in disregard of that provision. In particular, as regards the transfer of the shareholding of a company, the Court of Justice clarified that restoring the previous situation will entail, as the case may be, the reversal of that transfer by reassigning that shareholding to the original owner, and the neutralisation of the effects of that transfer.”

Procedural issues

Belgian Excess Profit: “The General Court annulled the Commission’s 2016 decision which held that Belgium had granted selective tax advantages under its “excess profit” tax scheme. The Court did not take a position on whether or not the scheme analysed gave rise to illegal State aid but found that the Commission had failed to establish the existence of an aid scheme. According to the General Court, when granting an excess profit ruling the Belgian tax authorities had a margin of discretion that necessitates a case-by-case assessment and which undermines an alleged systematic approach by the Belgian tax authorities, required for the existence of an aid scheme. This means that, according to the General Court, the tax rulings need to be assessed individually under EU State aid rules.”

BMW: “The Court of Justice confirmed the Eesti Pagar judgment in stating that national authorities can only check compliance of the aid measure with the GBER requirements, which entails procedural consequences on the obligation to notify or not. A finding of compliance with the GBER by a Member State offers at most a presumption of compatibility of the aid with the internal market.”

[1] The report can be accessed at:

http://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/annual_report/2019/part1_en.pdf

[2] The Staff Working Document can be accessed at:

http://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/annual_report/2019/part2_en.pdf

Photo by Steve Buissinne on Pixabay.