Mid-August 2020, a series of events unfolded in a short period of time. They may prove a watershed moment for the role of antitrust in regulating digital markets.

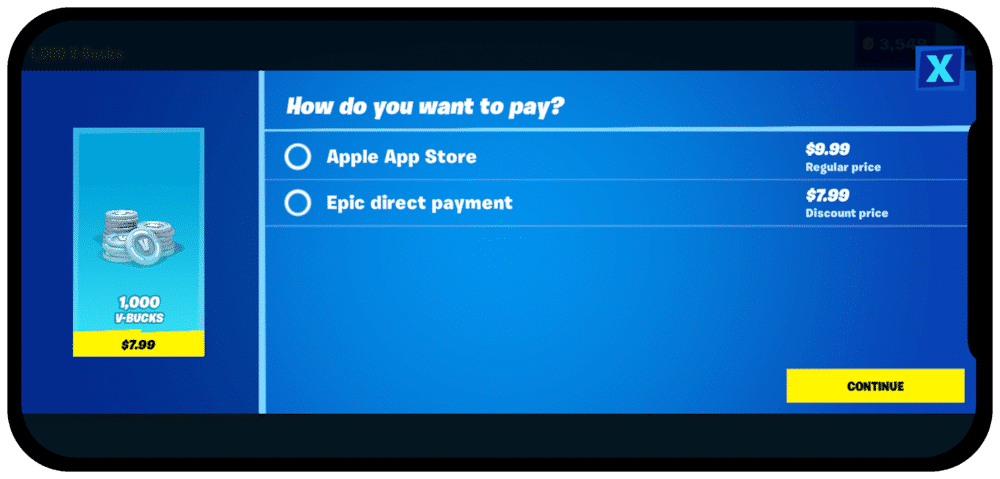

It started when gamers playing Fortnite on their iPhone were suddenly faced with a new choice screen when buying in-app currency:

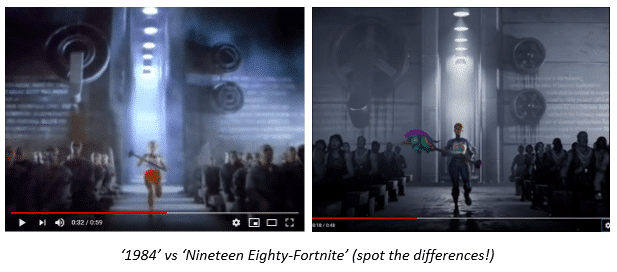

What changed is that Epic, the developer of Fortnite, introduced an alternative payment system next to Apple’s. Its alternative was cheaper: while Apple charges a 30% fee on in-app purchases, Epic charged only 10%, passing on 20% of cost savings to players. Apple quickly removed Fortnite from its App Store for bypassing the 30% fee—a violation of its Developer Guidelines. Epic had a carefully crafted response ready: It filed a 60-page complaint with the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. Epic also uploaded a video titled ‘Nineteen Eighty-Fortnite’—a parody of Apple’s iconic ‘1984’ commercial (which was directed at the monopolist of its time, IBM).

These are only the first shots in a larger battle that will rage on for some time. I believe that app stores are the quintessential online platform and that rulings in this area will have an outsized influence in shaping antitrust law in the digital era. Daniel Mândrescu and I also happen to have written a 60-page article on the topic: Assessing Abuse of Dominance in the Platform Economy: A Case Study of App Stores (available on SSRN and in the European Competition Journal). That is why we’re dedicating a series of posts to Epic v Apple, in which we combine our previous work with new-found insights.

The questions answered in this first blog post are introductory: Which Apple policies are at the heart of Epic’s complaint? And after years of similar complaints, why could this time be different?

The Apple ‘tax’

After the launch of the iPhone in 2007, Apple opened up its ecosystem to third-party developers in 2008 with the launch of the App Store. The announcement stressed that ‘applications must be approved by Apple and will be available exclusively through the App Store.’ On pricing, it noted: ‘Developers set the price for their applications—including free—and retain 70 percent of all sales revenues.’ In other words, Apple charges a 30% commission fee (or ‘tax’, according to critics).

Over time, the policy was modified slightly. Today, Apple’s in-app purchase system (‘IAP’) applies not only to app purchases, but also to in-app purchases and subscriptions. There are, however, some exceptions (set out in section 3.1 of the Developer Guidelines):

- Only purchases of/subscriptions to digital content must use IAP; it is not mandatory for in-app purchases of physical goods and services. This means Apple gets a cut from purchases of Fortnite currency or Spotify subscriptions, but not from Uber rides or Airbnb stays.

- So-called ‘reader’ apps (including newspaper, book, audio, music and video apps) may allow users to access content they previously purchased/subscribed to elsewhere. That is why you can subscribe to Netflix or Spotify through your web browser and then log in to your app. However, app developers are not allowed to inform their users of such alternative options (the ‘anti-circumvention rule’).

- The commission fee on subscriptions decreases to 15% after the first year.

Apple’s policy become the standard for the industry as other app stores followed its example (see e.g. Google’s Developer Program Policy, section ‘Monetization and ads’).

The list of developers dissatisfied with Apple’s level of commission fees, coupled with a prohibition to use other payment mechanisms, is long. A growing number of apps—including Netflix, Amazon’s Kindle, and Google’s YouTube TV—have simply disabled IAP, making it impossible for consumers to purchase/subscribe within the app. A new e-mail app, HEY, tried to disable IAP as well but was kicked out of the App Store for doing so because it did not qualify as ‘reader’ app, and is thus obliged to use IAP.

Until recently, Apple could say that its IAP policy was applied equally to all developers. During an investigation of the U.S. House Antitrust Subcommittee, however, it became clear that exemptions do exist: Apple lowered the commission fee for Amazon’s Prime Video from 30 to 15%. Major newspapers are already asking what it would take for them to get a similar deal.

So, complaints have been coming in for years—what makes Epic different? It may just be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Also, Epic chose to take the route of private enforcement in the U.S., while most other developers have instead chosen to submit complaints to the European Commission in hopes of spurring public enforcement. However, Epic is also in a unique position as a complainant. To understand why, we need take a closer look at the gaming industry.

The gaming industry—and Epic’s plans for it

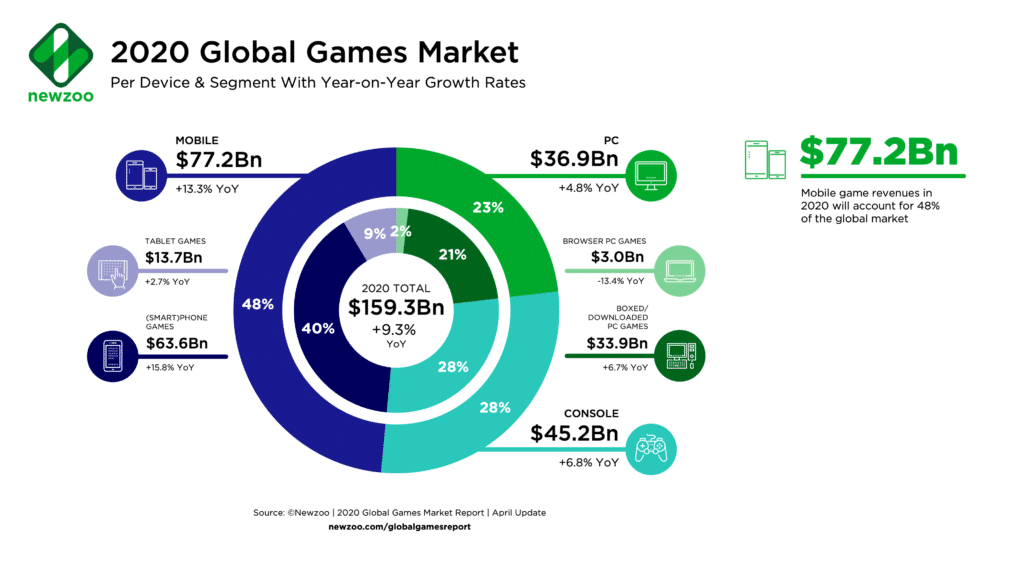

The gaming industry is big—perhaps surprisingly so. Since 2016, it has been larger than the music industry and box office combined. Take, for example, these numbers from 2019:

This year, the global games market is estimated to generate US$152.1 billion from 2.5 billion gamers around the world. By comparison, the global box office industry was worth US$41.7 billion while global music revenues reached US$19.1 billion in 2018.

Growth has only accelerated during the pandemic. As The New York Times put it: ‘People aren’t reading or watching movies. They’re gaming.’

The gaming industry can be divided into three segments (see chart below): console (e.g. Microsoft’s Xbox, Sony’s PlayStation, Nintendo Switch), personal computer (PC), and mobile. Within each segment, a distinction can be made between developing/publishing the game (content) and offering a platform to distribute it (distribution). The largest game companies by revenue are generally those that have a hand in both content and distribution (e.g. Sony, the 2nd largest game company). However, the 3rd largest game company is Apple, which is almost solely thanks to the 30% commission charged by the App Store for game distribution.

What about the largest game company? It’s the Chinese tech conglomerate Tencent, which operates the PC gaming platform WeGame, serves as a gateway to the Chinese market for non-Chinese developers/publishers, and owns or has a stake in a variety of game developers/publishers (e.g. Riot Games, Supercell, Activision and Ubisoft). In 2012, Tencent also took a 40% stake in Epic (Sony invested 2 months ago).

If there is one lesson to be drawn from the above, it’s that the saying ‘content is king’ is no longer true—rather, distribution is king. Epic has realized this. It disrupted PC game distribution by launching its own platform (the Epic Store) with a 12% commission fee, which put significant pressure on the 30% fee charged by the incumbent Valve (Steam). However, it cannot do the same for mobile, given that Apple’s guidelines prohibit ‘creating an interface for displaying third-party apps … similar to the App Store’ and iOS makes it technically impossible. Epic does support a variety of other games available on iOS through its ‘Unreal Engine’, a set of tools that facilitates the creation of 3D graphics.

Epic’s plans don’t stop at mobile distribution. The long game is to create a so-called ‘metaverse’, ‘a shared, virtual space that’s persistently online and active, even without people logging in. It will have its own economy, complete with jobs, shopping areas and media to consume.’ (Science fiction fans will recognize the concept from Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash or Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One). With Fortnite, Epic is closer than anyone to such a metaverse: it is already hosting live events including concerts and movies, while the game proceeds in ‘seasons’.

While the metaverse is still some time away, a more immediate innovation is cloud gaming: ‘a type of online gaming that runs games on remote servers and streams them directly to a user’s device’ (one benefit being that your device must not be state-of-the-art in order to play advanced games). But Microsoft’s xCloud—a ‘Netflix for games’ that gives subscribers access to 100+ games—is not allowed on the App Store: Apple decrees that every game must be submitted individually, which of course beats the purpose of xCloud. It is no surprise then that Microsoft submitted a declaration in support of Epic.

After the first shots, the first battle

Days after Epic submitted its complaint to the U.S. District Court, it filed a motion for a temporary restraining order. Apple had not only removed Fortnite from the App Store but also revoked all developer tools, which makes updates to other programs—including the Unreal Engine—impossible.

When it came to the Fortnite removal, the judge had little sympathy. She noted that ‘Epic Games made the calculated decision to breach its [developer] agreements with Apple’. Given that ‘the current predicament appears of its own making’, Epic did not demonstrate irreparable harm, and Apple does not have to reinstate it in the App Store.

Apple’s revocation of all developer tools was considered different. Epic’s access to those tools relies on ‘separate developer program license agreements with Apple and those agreements have not been breached.’ Moreover, Apple’s conduct is not only detrimental to Unreal Engine, but also affects many other developers who have built their games using the engine. According to the judge, ‘Epic Games and Apple are at liberty to litigate against each other, but their dispute should not create havoc to bystanders.’

Further in this series

There are a lot of battles left in this war, which we’ll cover on this blog. Outstanding questions include: Why is the focus on Apple—hasn’t a complaint against Google been filed as well? (Yes, but important differences do exist between these two mobile ecosystems.) Could iOS be considered an essential facility that developers should get access to, even to set up their own app store? How should the apparent tie between the App Store and IAP be assessed? Which steps, if any, are reasonable or recommended to halt anticompetitive app store conduct?

And finally, how is all of this relevant for EU competition law? You guessed it: the on-going Commission investigations into the App Store and Apple Pay. Those are driven in part by Spotify, which was quick to support Epic’s complaint against Apple. (Spotify v Apple serves as a case study in our aforementioned article, so if you can’t wait for answers, take a look at it here.)

And the Commission is not the only one paying attention. The head of Germany’s Federal Cartel Office said Epic v Apple ‘has most certainly attracted our interest’. ‘We are at the beginning, but we are looking at this very closely.’ So are we!