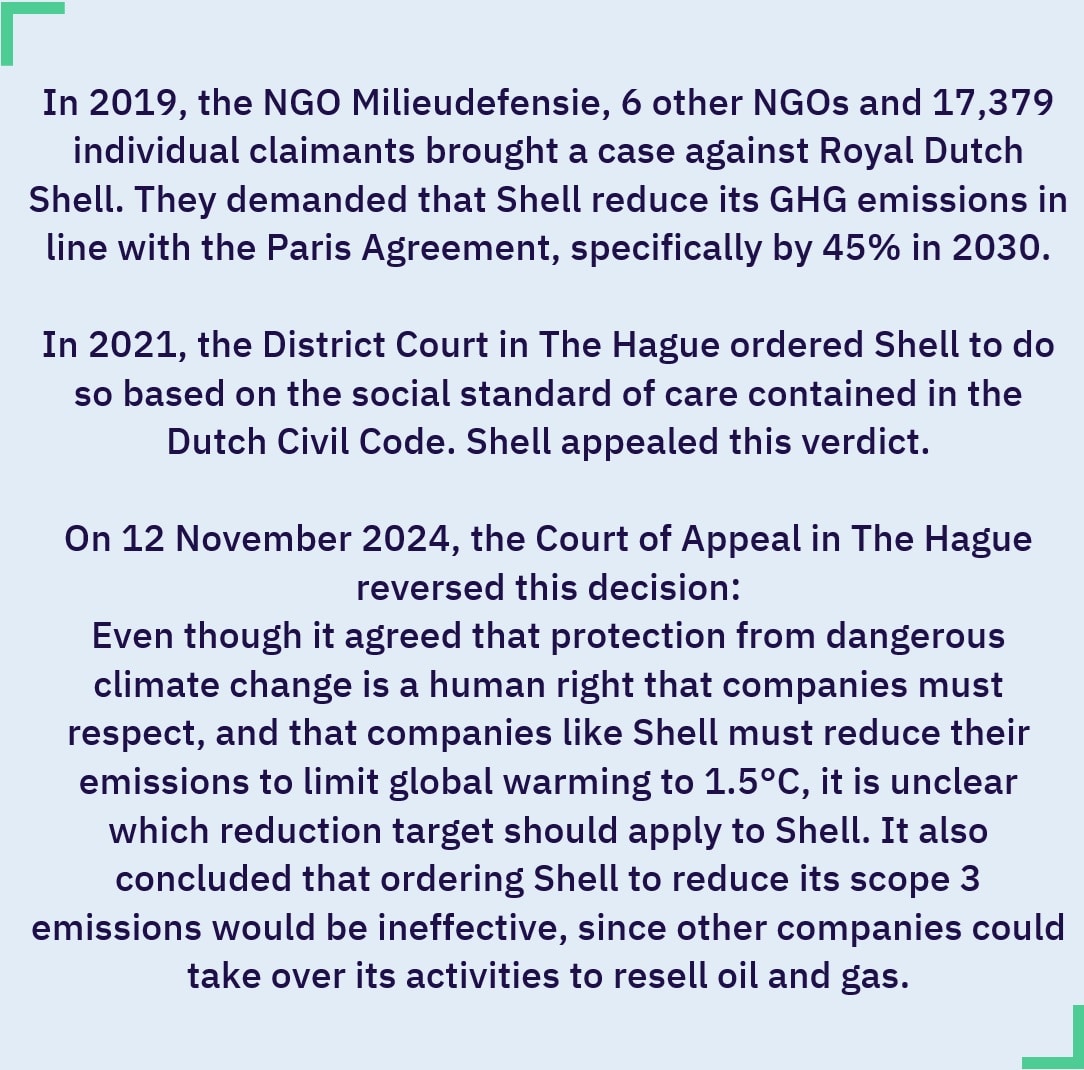

In this case, the Court:

1. Concluded that all companies, and especially those whose products have contributed to climate change like Shell, have an obligation to do their part by reducing their emissions to limit global warming to 1.5°C as determined in the Paris Agreement. This is based on an unwritten social standard of care required from all persons, including companies, under article 6:162 of the Dutch Civil Code (DCC);

2. Clarified that such a social standard of care to reduce emissions extends beyond what is required of companies under EU legislation;

3. Indicated that Shell’s investments in new oil and gas production may violate the standard of care by highlighting the need for taking measures to reduce fossil fuel supply and the responsibility of fossil fuel producers in this regard. However, the Court stopped short of a declaration on this as it was not part of the claim;

4. Dismissed the claim that Shell should be ordered to reduce its scope 1 and 2 emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2019, since the Court was satisfied with Shell’s aim to reduce emissions by 48% by then;

5. Also dismissed the claim that Shell should reduce its scope 3 emissions by 45%. The Court stated that it is unclear how the global average reduction standard of 45% should be applied to a company like Shell since different sectors and countries need to reduce their emissions at different speeds, and there also seems to be no consensus on particular emission reduction standards for the oil and gas sector. It further noted that ordering Shell to reduce its scope 3 emissions would be ineffective, since other companies could replace Shell’s activities to buy and resell oil and gas, cancelling out the impact of the order.

(1) Companies have a responsibility to reduce their emissions

The Court explained that the indirect horizontal effect of human rights means that human rights do not just apply “vertically”, between citizens and their governments, but may also influence the “horizontal” relationships between citizens and private companies. Courts may therefore use human rights to interpret concepts from private law, such as the unwritten social standard of care required under article 6:162 of the Dutch Civil Code or DCC. As the Prosecutor General highlighted in the Urgenda case, this is because open norms in Dutch national law can be interpreted using other sources like treaties, soft law instruments and science, similar to how the human rights contained in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) can be interpreted.[1] The Supreme Court in the Urgenda case determined that different sources constituted a “widely endorsed consensus” which could be used to interpret the obligations of the government. The District Court in this case did the same to interpret the unwritten standard of care required under article 6:162 DCC.[2] The Court of Appeal therefore also looked for consensus in a variety of sources to interpret the standard of care, beginning with human rights.

Article 6:162 DCC

-

A person who commits a tortious act (unlawful act) against another person that can be attributed to him, must repair the damage that this other person has suffered as a result thereof.

-

As a tortious act is regarded a violation of someone else’s right (entitlement) and an act or omission in violation of a duty imposed by law or of what according to unwritten law has to be regarded as proper social conduct, always as far as there was no justification for this behaviour.

-

A tortious act can be attributed to the tortfeasor [the person committing the tortious act] if it results from his fault or from a cause for which he is accountable by virtue of law or generally accepted principles (common opinion).[3]

The Court confirmed that protection from climate change is a human right as stipulated in the Dutch Supreme Court’s judgment in the Urgenda case, (based on articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR), the KlimaSeniorinnen case of the European Court of Human Rights (based on article 8 ECHR), as well as judgments from courts in Pakistan, Colombia, Brazil, the US and India.[4] It also based this confirmation on resolutions by the UN Human Rights Council and the UN General Assembly in which the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is recognised as a human right. The Court stated that “there is no doubt that the climate problem is the greatest issue of our time”.

The Court further cited the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct and the accompanying commentary that companies should respect human rights, take measures to prevent violations of human rights and set targets for reducing their scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.

-

Scope 1 refers to direct emissions from facilities that are owned or controlled by the company;

-

Scope 2 to indirect emissions caused by the generation of electricity that has been bought and used by the company; and

-

Scope 3 to the emissions that follow from the activities of the company, such as the burning of oil and gas that was produced by the company by others.

The Court also referred to other non-binding instruments specifying that companies have a responsibility to reduce their (scope 1, 2 and 3) emissions by 2030 either substantially or by “a fair share of” the global reduction needed to limit warming to 1.5°C. All this led the Court to conclude that there is a consensus about the standard of care required, namely that especially companies whose products have contributed to climate change, like Shell’s fossil fuels, have a responsibility to contribute to achieving the Paris Agreement targets by reducing their emissions. In the Court’s interpretation of the social standard of care under 6:162 DCC, companies have a legal obligation to reduce their emissions, even if this obligation is not explicit in the law. Shell’s size and impact mean that its responsibility is larger than that of most other companies.

(2) Companies have a duty of care to reduce their emissions even if they comply with EU legislation

Since the decision of the District Court was published in 2021, the EU has created and amended climate legislation as part of the European Green Deal, like the Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), EU ETS2, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). Some parts of Shell’s emissions in the EU fall under the emission caps of the EU ETS and the ETS2. The CSRD and CSDDD contain procedural obligations for companies like Shell. They must report on how they intend to contribute to keeping global warming below 1.5°C and reaching net zero by 2050 and must adopt a transition plan for climate change mitigation with the same aims. However, neither the ETS and ETS2 nor the corporate directives set absolute reduction targets for companies like Shell. Although this package of legislation is intended to implement the EU’s 2030 reduction target of -55%, the Court did not consider it to be exhaustive and found that, even if companies comply with this legislation, they also have a separate “social duty of care to reduce their emissions” based on the social standard of care under article 6:162 DCC.

(3) Investments in new oil and gas may violate the standard of care

Based on climate science, the Court stated that it is likely that to limit global warming to well below 2°C, measures need to be taken to reduce both fossil fuel demand and supply. It also acknowledged that Shell knows about the risk of carbon lock-in, which means that since fossil fuel infrastructure is very expensive to build, fossil fuel producers want to use it for as long as possible to get a return on their investment, slowing down the energy transition. Based on the social standard of care under article 6.126 DCC, as interpreted through articles 2 and 8 ECHR and the UNGP and OECD guidelines, fossil fuel producers must take responsibility for limiting fossil fuel supply. However, the Court indicated that, although Shell’s investments in new oil and gas may violate the standard of care, no decision was necessary on this question as it did not form part of the claimants’ action.

(4) Scope 1 and 2 emissions

The Court dismissed the claim that Shell should reduce its scope 1 and 2 emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2019, since Shell aims to reduce them by 50% by 2030 compared to 2016 (which is 48% compared to 2019) and has already achieved a 31% reduction. The Court did not accept the claimants’ argument that Shell has changed its policy before, and that this reduction may therefore not be achieved and/or not be permanent.

(5) Scope 3 emissions: no clear reduction standard and not an effective order

The Court also dismissed the claimants’ demand that Shell should reduce its scope 3 emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2019, even though Shell has a “special responsibility” as a large oil company and is legally obligated to reduce these emissions. Without a scientific consensus on a reduction target that applies to companies like Shell, the Court found that it was unable to accept this claim as long as legislation does not provide such a target. The claim was based on the IPCC’s finding that global emissions need to go down by 45% by 2030 for a 50% chance of keeping global warming below 1.5°C. Even though the Court agreed with this finding, it could not come to a decision on what this means for Shell’s reduction target since different sectors and countries must reduce their emissions at different speeds. The Court claimed that burning gas is less damaging to the climate than burning coal, so it assumed that replacing coal with gas supplied by Shell would increase Shell’s scope 3 emissions but also lead to an emission reduction globally. The Court also pointed to the fact that emissions must be reduced at different speeds in the sectors where Shell’s products are used, like transport and buildings. It could therefore not apply the general reduction target of 45% to Shell’s scope 3 emissions across the board. The Court was also unable to determine a sufficiently supported reduction standard for the oil and gas sector, since different reports suggest different percentages.

The Court found that ordering Shell to reduce its scope 3 emissions would not be effective, since other companies would take over its activities to buy and resell oil and gas. Shell argued that it has no responsibility for scope 3 emissions, since it is the end-users and not Shell who decide which sources of energy to use. The Court rejected this argument partly because Shell has itself adopted scope 3 reduction targets. Shell also argued that two-thirds of its scope 3 emissions do not come from oil and gas that it has produced, but that it has bought from others and then resold. If Shell stopped reselling to comply with a reduction obligation, other parties could take over these activities and total emissions would not be reduced. The Court stated that although limiting fossil fuel production may lead to reduced emissions, the same cannot be assumed for limiting the sale of fossil fuels. Since reducing Shell’s scope 3 emissions by limiting its resale activities would not serve the interest that the claimants are pursuing with this case, namely protecting Dutch residents against climate change, the Court found that an order regarding scope 3 emissions would not be effective.

Climate change litigation implications

The Shell case falls under C2LI scenario 3: in this case several NGOs and individuals challenged a company’s business policy because of its impact on climate change. Some important implications of the Court of Appeals’ decision are as follows:

On the one hand, it is a setback for climate litigation that the Court of Appeal reversed the decision of the District Court that Shell should reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030. The District Court’s decision in 2021 sent a clear message that it is not just up to states to limit global warming, but that companies have a responsibility too, and that it can be quantified. Similar cases have since been brought in other countries, demonstrating an impact that goes beyond Shell and beyond the Netherlands. The fact that on appeal, the Court did not order Shell to reduce its emissions because it was not able to determine how much would be required could lead courts in other countries to come to the same conclusion in similar cases. It might also lead some companies to conclude that, unless the state imposes concrete reduction obligations on them, they can continue with business as usual. This may lead to delays in reducing emissions and achieving net zero.

On the other hand, it is progress that the Court confirmed that companies, and especially those providing products that contribute to climate change, do have a legal obligation to reduce their emissions in line with the Paris climate goals. Importantly, this obligation does not just include their own emissions (scope 1 and 2), but also the emissions of their customers, meaning their scope 3 emissions. The judgment is therefore not a complete victory for Shell. Over the years, there has been a lot of discussion whether companies can be held responsible for the emissions caused by the use of their products. However, unless Shell appeals this part of the judgment, the Court has now settled this discussion in the Netherlands. Claimants in other jurisdictions could use this argument to demand that companies reduce their scope 3 emissions. It may also provide opportunities for new climate cases in the Netherlands itself. The obligation for companies to reduce their emissions could, for example, be used against companies in sectors where consensus about the reduction standard already exists or where more clarity about standards emerges. Scientists and international bodies that set reduction standards may be able to provide such clarity.

Another possible advance is the Court’s finding that the fossil fuel supply will likely need to be limited to achieve the Paris climate goals and that producers have a responsibility in this regard. The Court seems to suggest that Shell’s continued investment in new oil and gas could be a violation of the Dutch standard of care. This could mean that the Court believes that a standard does exist when it comes to (the financing of) (new) oil and gas production, which could also provide opportunities for new climate litigation. A case demanding that Shell or another fossil fuel company reduce investment in and/or the production of (new) oil and gas may therefore well succeed. This, in fact, is one of Milieudefensie’s demands in its case against the bank ING.

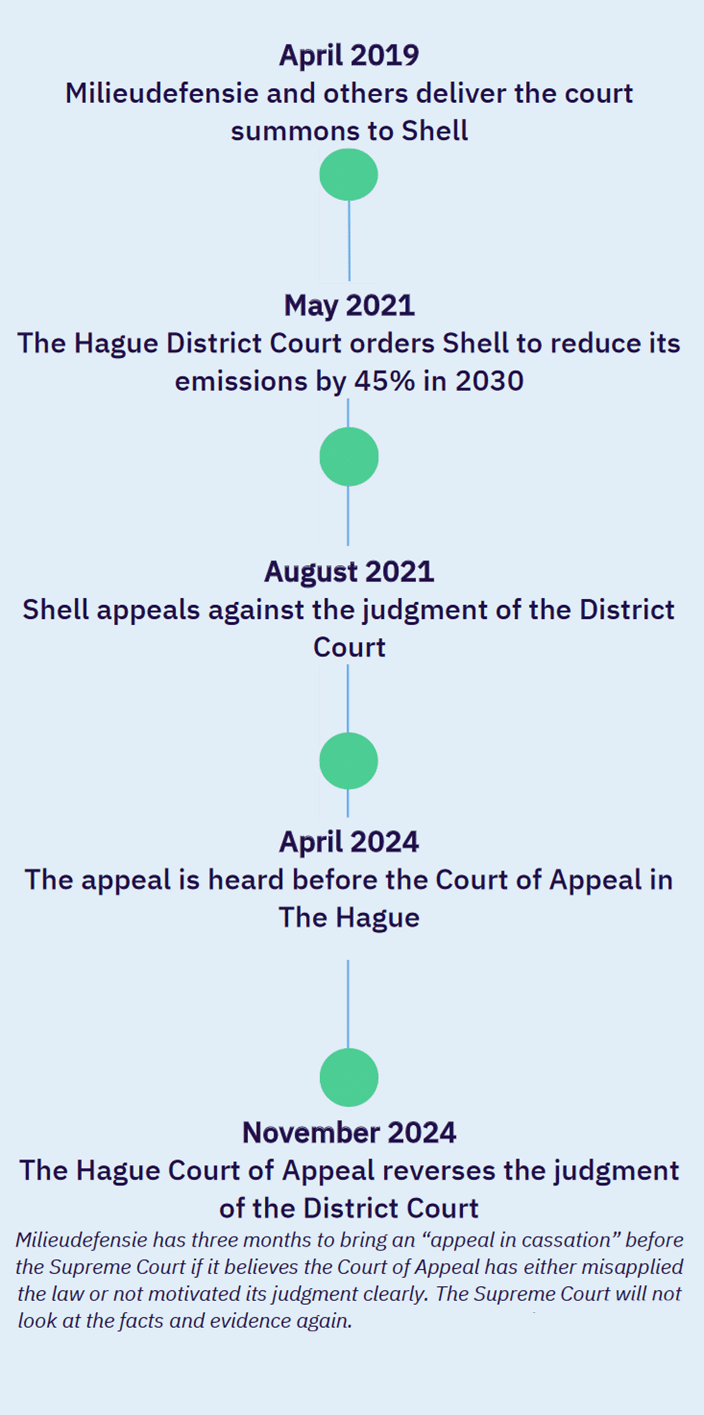

Milieudefensie seems to have won the legal argument, namely that Shell has a legal obligation to reduce its scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, but lost on the facts, because the Court was unable to determine a concrete scope 3 reduction standard that applies to Shell. This may make it difficult for Milieudefensie to bring an appeal in cassation before the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court will only consider whether the Court of Appeal has made an error in applying the law or failed to properly motivate its judgment. It will not examine the evidence again. It is therefore unclear whether Milieudefensie will be able to formulate grounds on which to appeal the judgment.

[1] Government of the Netherlands (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy) v. Urgenda Foundation, no. 19/00135, ECLI:NL:HR:2019:2006, 20 December 2019, (English translation ECLI:NL:HR:2019:2007, published 13 January 2020), Hoge Raad (Supreme Court) (Urgenda Supreme Court) [5.4.2-3]; Conclusion Prosecutor General, ECLI:NL:PHR:2019:887 <https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/details?id=ECLI:NL:PHR:2019:887>, regarding Supreme Court 20 December 2019 [2.30-31].

[2] Urgenda Supreme Court (n 1) [7.2.1-11]; Vereniging Milieudefensie and Others v Royal Dutch Shell, no. C/09/571932, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5337, 26 May 2021 (English translation ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339), Rechtbank Den Haag (The Hague District Court) (Milieudefensie v Shell) [4.4.1-4.4.55].

[3] Unofficial translation from http://www.dutchcivillaw.com/legislation/dcctitle6633.htm.

[4] Lahore Hight Court 4 September 2015, case no. W.P. No. 25501/2015, par. 7 (Leghari/Federation of Pakistan); Supreme Court of Colombia 5 April 2018, no. STC4360-2018, p. 13 (Future Generations/Ministry of the Environment); Federal Supreme Court of Brazil 7 April 2022 (PSB et al v. Brazil); Montana First Judicial District Court 14 August 2023, case no. CDV-2020-307, p. 97-98 (Held, et al./State of Montana, et al.) and Supreme Court of India 21 March 2024, Civil Appeal no. 3570 of 2022, par. 20 (Ranjitsinh and Others v Union of India and Others).