- Infrastructure. It is argued that Dinamo, the main tenant using Stadium Maksimir, uses the City of Zagreb owned stadium at no cost. This is because the annual rent corresponds with the annual maintenance costs of the stadium, and these maintenance costs are provided by the City of Zagreb (along with maintenance costs for the academy, “Hitrec Kacijan”). The stadium is primarily a football stadium; however it is multifunctional in the sense that Dinamo must make the stadium available for other uses, such as music concerts.

- The development of young talent. The buying and selling of young players is central to Dinamo’s financial operations. The club’s finances have benefited from developing talent, and selling it on, for example Mateo Kovačić (to Inter Milan), Tin Jedvaj (to Roma), and Alen Halilovic (to Barcelona for EUR 2.2m). However, the complaint suggests that the cost of training young players, part of the youth academy at Dinamo, is borne seemingly entirely by the City of Zagreb.

- International competitions. Dinamo regularly features in UEFA sanctioned European club competitions, e.g. the Champions League and Europa League. The complaint alleges that the City of Zagreb financially enables the club to participate in these Europe-wide competitions, e.g. covering the costs of attending away games and staging home games.

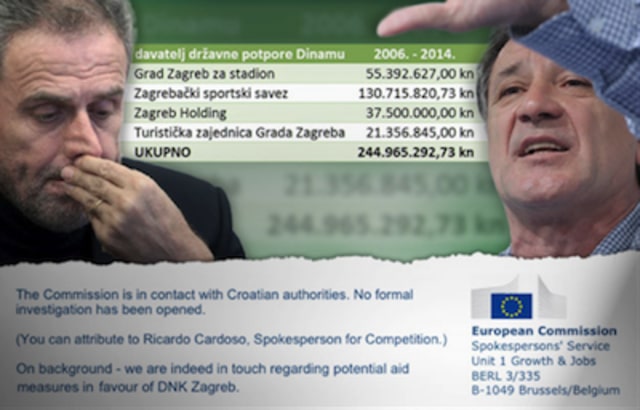

In total, it is alleged that GNK Dinamo received €30 million between 2006 and 2014. However, because obligations under Article 107 and 108 TFEU were only applicable to the City of Zagreb following Croatia’s 2013 EU accession, the actual amount recoverable is most likely significantly less than the headline figure. Despite this, there is no indication of the alleged aid abating, nor do any notifications appear forthcoming.

Do you know we also publish a journal on State aid?

The European State Aid Law Quarterly is available online and in print, and our subscribers benefit from a reduced price for our events.

The complaint suggests the City of Zagreb’s justification for the support is simply down to the market (e.g. through sponsorship) not providing sufficiently stable funding to maintain high quality professional football at Dinamo, which is viewed to encourage the development of sport generally and contribute to the national and international reputation of Zagreb. Therefore, in a similar way to the Dutch and Spanish cases (referred to above), the Dinamo complaint raises questions concerning how, and the manner in which, professional football clubs – powerful brands in communities – may be harnessed by government, and, in addition, why, so often, with respect to compliance with notification and approval obligations, government regards professional sport differently from other business sectors.

The Dinamo case, at first glance, does not appear especially remarkable, or indeed worthy of comment, but it highlights a complicated situation and a number of interesting areas for debate. In Croatia, the professional side of football is less mature than in other Member States, such as the Netherlands and Spain. Also, despite the stabilisation and association process initiated in 1999, Croatia must, to an extent, still be acclimatising to EU membership. As a consequence, close economic ties between professional football clubs and government are understandable, and potential problems in this area have been recognised by the Croatian legislature: a paragraph of text was inserted into Croatia’s Sports Act in July 2013 reminding local authorities of the need for compliance with EU State aid rules (see Art.74, para.3). This move was reported on recently by Tatjana Jakovljevic (Croatian Competition Agency) in the European State Aid Law Quarterly (‘Public Support for Sports: The Name of the Game – Football!’ (2013) 12(3)); however, it does not appear yet to have had any meaningful impact on the ground, i.e. triggering notifications, and one can speculate that in all likelihood unlawful State aid is quite widespread in professional sport in Croatia.

The Dinamo case is also interesting because of the origins of the complaint: a small band of determined and resourceful supporters of a rival football club, Hajduk Split. This is a club, which itself has suffered as a “firm in difficulty”, and was treated as such by Croatia’s Competition Agency under Croatia’s State Aid Act. Arguably, this complaint activity highlights something unique about the sector (professional football): impassioned supporters willing to explore all avenues to ensure a level playing field (the author invites comments on this specific point). These particular supporters, who are actually minority shareholders of Hajduk Split, have forced the issue into the national press, and have even had politicians debating the subject: a round table discussion was held by the Croatia’s Ministry of Justice at the Croatian Parliament, the Sabor, on 11th February 2015. The attendees of the round table event included government ministers, parliamentarians, the Croatian Competition Agency, Transparency International and academics.

The complaint’s football backdrop has drawn attention to State aid law like few other business sectors could, and looks set to trigger broader reform, e.g. encouraging wider acceptance of the notification and approvals system and the production of general guidance informed by the experience in other Member States.

Suggested citation:

R Craven, ‘State Aid to Football clubs in Croatia?’ (State Aid Hub Blog, 16th February 2015) <http://stateaidhub.eu/blogs/stateaid/post/1337>

About the contributor:

Dr Richard Craven, Northumbria Law School ([email protected])

Photomontage: Hina, located here.

Links

- http://ec.europa.eu/competition/elojade/isef/case_details.cfm?proc_code=3_SA_33584

- http://ec.europa.eu/competition/elojade/isef/case_details.cfm?proc_code=3_SA_29769

- http://ec.europa.eu/competition/elojade/isef/case_details.cfm?proc_code=3_SA_33754

- http://ec.europa.eu/competition/elojade/isef/case_details.cfm?proc_code=3_SA_36387

- http://www.aztn.hr/uploads/documents/eng/documents/decision/DP/UPI-430-012013-05001.pdf

- http://www.asser.nl/SportsLaw/Blog/post/state-aid-in-croatia-and-the-dinamo-zagreb-case

- http://public.mzos.hr/Default.aspx?sec=2545

- http://www.lexxion.de/en/verlagsprogramm-shop/details/3561/17/estal/news-from-the-member-states

- http://dalmatinskiportal.hr/vijesti/okrugli-stol-o-potporama-u-sportu-financiranje-skautske-sluzbe-u-juznoj-americi-nije-javni-interes-/2682