This posting examines several recent measures which do not have a single common theme. However, each measure has unusual elements which should be of interest to State aid professionals.

Exceptional circumstances: Commission Decision 2013/197 on aid to Cantiere Navale De Poli (IT)[1]

The measure in question concerned State aid that Italy intended to provide to shipyard Cantiere Navale De Poli for the construction of a vessel. Under the relevant rules on aid to shipbuilding, aid has to be granted within a three-year period. In this particular case the three-year period was extended because of construction delays. The issue at hand was whether the delays were predictable or exceptional. In the latter case extension of the eligible period could have been justified.

The Commission examined the measure on the basis of the principles established by the General Court in case T-72/98, Astilleros Zamacona.[2] The Court held that it was for Member States to i) demonstrate that the alleged exceptional circumstances resulted in such significant disruption as to affect construction work and ii) to establish a causal link between the two events. The Commission interpreted the words “exceptional” to mean abnormal events or events that could not have been “reasonably” taken into account in the normal work plan of the shipyard. Some delays are normal in a three-year programme. By contrast, long delays in the delivery of critical parts can be considered exceptional.

In the end the Commission concluded that the Italian authorities failed to prove the exceptional nature of the delays. For this reason it found the aid to be incompatible with the internal market and ordered Italy not to implement the measure in question.

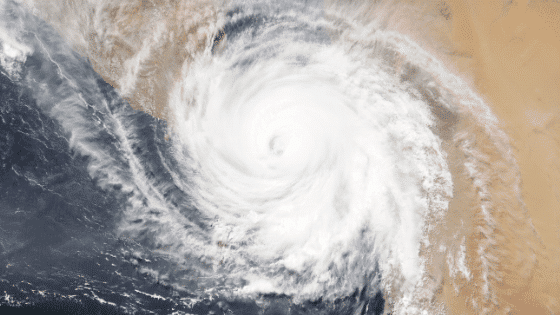

Natural disasters: Commission Decision SA.36027 on compensation of damage caused by future natural disasters in Valle d’Aosta (IT)[3]

This is an unusual measure because normally compensation is offered only after a natural disaster actually occurs. This scheme, however, covers disasters that have not yet occurred. It therefore acts like an insurance measure and its advantage is that the Italian authorities will be able to offer assistance immediately after a disaster without having to wait for the Commission’s approval. However, just as with any insurance measure, it runs the risk of creating moral hazard. Potential beneficiaries may take fewer precautions. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that the risk of moral hazard is mitigated by the fact that the scheme does not cover 100% of the damage.

The scheme which will expire in December 2018 covers all sectors, except agriculture and fisheries. Financing will be made available only in the event of actual damage and the scheme will be put into operation only after regional or national authorities declare a natural disaster. For the purposes of the scheme, a natural disaster is defined only as earthquake, landslide, flood or avalanche.

Eligible costs are only costs for material damage to property: buildings, machinery, equipment and stocks. Aid to compensate economic disadvantage, such as financial losses and foregone revenues, is excluded from the scope of the scheme.

The aid intensity may not exceed 70% of the eligible costs or 40% of the eligible costs in case the aided activity is not resumed or the assets are not restored. The maximum amount of aid per beneficiary may not exceed EUR 0.5 million. Any insurance pay-out is subtracted from the compensation.

The Commission approved the scheme on the basis of Article 107(2)(b) TFEU.

Do you know we also publish a journal on State aid?

The European State Aid Law Quarterly is available online and in print, and our subscribers benefit from a reduced price for our events.

Reduced commercial risk: Commission Decision 2013/198 on aid to Habidite Alonsogeti (ES)[4]

Habidite Alonsogeti (HA) was involved in the construction of social housing. It received aid for purchasing land and for the construction of the housing units. The Commission assessed the compatibility of the aid on the basis of the regional aid guidelines [not the SGEI Decision or Framework].

What makes this case interesting is the determination of the existence of aid and the quantification of the aid amount. For the purchase of land, HA received two kinds of aid: relief from the costs of adapting the land for the purposes of construction of special units and a four-year grace period in the payment of the price. In relation to the grace period, the Commission calculated the aid amount as being equivalent to that of an interest-free loan.

However, the Commission applied the rules in force at the time the aid was granted. In this case the relevant rules were the Commission Notice on reference rate of 1997. Normally, to determine the amount of aid in a loan, a risk premium has to be added to the base rate [normally, the inter-bank offer rate] applicable for each country. The Commission Notice of 1997 did not provide for top-ups to be added to the base rate so as to reflect the credit risk profile of HA. “Under the 1997 Commission Notice, reference rates were considered to reflect the average level of interest rates charged in the various Member States on medium- and long-term loans (five to ten years) backed by normal security. … In the absence of direct information on the credit risk rating of HA, the Commission considers that it can be assumed that HA qualified at the time as a normal company with normal collateralisation.” [paragraph 75]. On these grounds the Commission took 4.36% as the reference rate, which was Spain’s base rate at the time, without any risk premium and concluded that the aid amount was equivalent to 13.6% of the purchase price.

The aid for the construction of housing units also had an unusual element. HA sold 1500 units to the local authority for a price below the prevailing market prices [EUR 2000/sqm as opposed to EUR 2900/sqm]. Apparently it received no advantage.

However, the Commission considered that HA did derive an advantage because i) the risk on a sizeable proportion of the project [1500 units] was eliminated and because ii) the sale price was still above the cost of construction incurred by HA.

The local authority was not considered to act as a private investor because it did not have a commercial need for 1500 units.

The amount of aid involved in the contract was “defined as the profit that would have been obtained by HA from the sale of the 1500 homes to the [local authority] under the terms of the Houses Contract, namely, the difference between the price to be obtained from the [local authority] from the sale of the 1500 houses under the pricing terms stipulated by Article A(e) of the Houses Contract the Houses Contract and HA’s production costs for the 1500 houses.” [paragraph 107]

While the logic of the Commission is correct, its method is questionable and varies significantly from other recent cases where the Commission applied more thorough and more economically robust methods. For example, there is no attempt to quantify the benefits from reduced risk. There is also no consideration of “normal profit” and the cost of capital borne by HA.

Such unexplained variations in methodologies reduce legal certainty for notifying authorities which do not know what calculations the Commission would expect them to carry out.

In the end the Commission concluded that the aid in the land purchase was compatible with the internal market under the regional aid guidelines. The aid in the construction and sale of houses was incompatible with the internal market.

Rights of Complainants Concerning Unlawful Aid: Case C‑615/11 P, European Commission v Ryanair, 16 May 2013[5]

The European Commission appealed against the judgment of the General Court in case T‑442/07 Ryanair v Commission. The General Court had found that the Commission did not fulfil its obligations under the Treaty because it failed to adopt a decision in respect of the transfer of 100 employees of Alitalia which was the subject of a complaint set out in a letter of 16 June 2006 that was sent to the Commission by Ryanair.

According to Article 10(1) of the procedural regulation [Regulation 659/1999], “where the Commission has in its possession information from whatever source regarding alleged unlawful aid, it shall examine that information without delay.” Article 20(2) of the same regulation provides that “any interested party may inform the Commission of any alleged unlawful aid and any alleged misuse of aid.” The unconditional nature of these provisions have caused headaches for the Commission which receives many complaints some of which are either bogus or based on misunderstanding of the facts and the scope of application of Article 107(1) TFEU. This is the reason why under the current State Aid Modernisation initiative, the Commission wants to be given more leeway to reject complaints.

However, as the law stands today, the Commission is required immediately to examine the possible existence of aid and its compatibility with the internal market. If, after it considers a complaint, the Commission believes that there are not grounds for investigating further, it must inform complaints accordingly and, according to the Court of Justice, it “must also allow those parties to submit additional comments within a reasonable period” [paragraph 29]

Furthermore, the Commission must close the preliminary examination of a complaints concerning unlawful State aid by adopting a decision. Such a decision must lead to one of three possible conclusions: i) there is no aid, or ii), if there is aid, the aid is compatible, or iii) there are serious doubts about its compatibility and as a consequence the formal investigation procedure is launched. This decision is based on the information which is provided by the complaint. As mentioned above, the requirements of Regulation 659/99 leave very little room for discretion to the Commission to reject complaints which appear not to be well founded. It is often bound to open the formal investigation procedure which is time consuming and cumbersome.

The Court of Justice, as to be expected, showed little sympathy with the Commission’s argument that the General Court relied on the subjective intention of Ryanair and that Ryanair did not prove how the transfer of Alitalia employees could constitute State aid. The Court set the following standard for the nature of information that complainants need to provide in the letters they send to the Commission. “Notwithstanding its brevity, such a letter, by the nature and the wording of the information transmitted, must be regarded as enabling the Commission to identify, with sufficient precision, inter alia, the presumed beneficiary of the alleged unlawful aid, the nature of the advantage at issue and the mechanism by means of which that advantage has been granted.” [paragraph 36]

This is not a high standard and unless the Council agrees to revise the procedural regulation, the Commission will continue to be obliged to examine and formally decide on most complaints it receives.

———————————————–

[1] OJ L119, 30/4/2013. It can be accessed at:

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:119:0001:0008:EN:PDF

[2] The judgment can be accessed at:

[3] It can be accessed at:

http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/247271/247271_1426788_67_2.pdf

[4] OJ L119, 30/4/2013. It can be accessed at:

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:119:0009:0029:EN:PDF

[5] it can be accessed at: