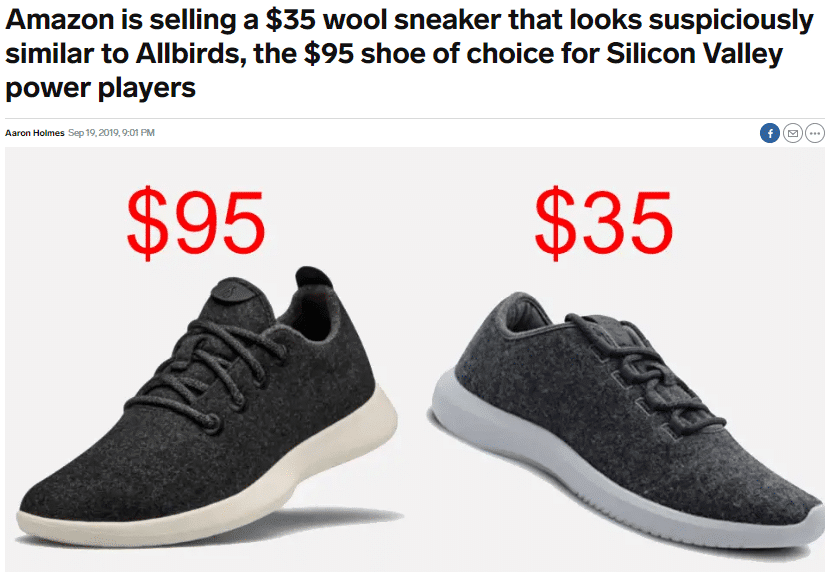

‘We have reached “peak cloning” in Silicon Valley’, read a recent tweet by Jeff Morris Jr. (Tinder’s director of product). ‘There are no rules anymore’, the author continued, ‘if you build a product that works, Amazon or Facebook will copy it.’ The tweet was prompted by the apparent copying by Amazon of Allbirds. Allbirds is a brand famous for its merino wool sneakers (‘the world’s most comfortable shoes’)—they launched on Kickstarter in 2014 and were recently valued at $1,4 billion.

The tweet clearly struck a nerve: not only did it go viral on Twitter, it was also covered by various publications including Business Insider (see image above), The Verge and Quartz. This was no coincidence, as the tweet fit neatly into an increasingly popular narrative: start-ups come up with innovative products, then the big tech firms simply steal their ideas and market a blatant copy. This dynamic has been called anticompetitive: in her plan to regulate big tech, for example, Senator Elizabeth Warren notes that ‘Amazon crushes small companies by copying the goods they sell on the Amazon Marketplace and then selling its own branded version.’

Given how the ‘move last and take things’ narrative is capturing the interest of both journalists and policymakers, it is high time to unpack it. In particular, it is worth asking when—if ever—the copying of a competitor’s product can be anticompetitive in the sense of antitrust law. To start this inquiry, it is necessary to first understand the meaning and prevalence of ‘copying’.

Who’s copying whom?

Every tech giant—and certainly GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple)—has been accused of copying competitors. Just a couple of weeks ago, for example, a news article reported ‘how Apple uses its App Store to copy the best ideas’. The main targets of such accusations, however, are Amazon and Facebook. Let us take a look at how these firms have allegedly copied competitors.

Observers have been aiming attention at how Amazon copies products offered by third-party sellers on its Marketplace for some time now. The fixation goes back to at least 2016, when a Bloomberg headline read: ‘Got a Hot Seller on Amazon? Prepare for E-Tailer to Make One Too’. The article focused on Rain Design, the distributor of a best-selling laptop stand on Amazon. At some point, Amazon started selling a similar stand under its AmazonBasics brand—at half the price. The story became a recurring theme in subsequent coverage of Amazon’s uneasy relationship with the third-party sellers on its platform (see e.g. here and here). Amazon’s alleged copying of furniture by Williams-Sonoma’s West Elm brand has also sparked reporting—and a lawsuit.

Of course, such anecdotes can at best illustrate—not demonstrate—a broader phenomenon. However, Amazon’s entry into the product spaces of third-party sellers has also attracted academic research. The available empirical evidence does suggest that Amazon uses the vast amount of sales data it collects on third-party transactions to guide its vertical integration from marketplace to retailer. Hagiu and Wright hold that ‘once Amazon reaches information parity with its sellers, it switches [from the marketplace] to the reseller mode in order to exploit its scale advantage’. In particular, Amazon chooses to vertically integrate in short-tail products (with a high sales volume), leaving the long-tail products to the retailers on its platform. Zhu and Liu confirm that Amazon vertical integration targets products with greater demand, and add that higher prices and lower shipping costs also guide the process.

While Amazon has made headlines and spurred research, Facebook has been the main target of the media’s ire. Just days ago, The Wall Street Journal scooped that Snap—the company behind the camera-based social network Snapchat—has detailed Facebook’s aggressive tactics in a dossier ominously named ‘Project Voldemort’ (see here for non-paywalled reporting). The report details how Facebook has Avada Kedavra’d Snap, among others by copying its most popular features.

The WSJ story didn’t exactly come as a surprise. Various news articles have already described how Facebook copied Snapchat’s characteristic ‘Stories’ feature on its three major platforms (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp). Other sources have pointed out how Snapchat’s user growth slowed considerably thereafter. Facebook is also said to have copied other applications including Tiny Houseparty (a video app) and Hinge (a dating app). Just like Amazon, this entry into spaces of third parties is apparently not random: Facebook bought Onavo, an app that tracks data usage on smartphones, and has used the aggregated data of its millions of users to direct its strategy.

Copying, especially by big tech and of start-ups, provokes strong feelings of unfairness. The question remains, however, whether it is anticompetitive in the antitrust sense of the word.

Is copying an antitrust problem?

While it is still unsure whether copying will lead to antitrust decisions, it has certainly sparked investigations. About a year ago, EU Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager announced an probe of Amazon, voicing a concern that Amazon uses third-party seller data for its calculations as to ‘what is the new big thing, what is it that people want, what kind of offers do they like to receive, what makes them buy things’ (see my discussion here). In the meantime, the investigation has been formalized, with the Commission stating that it is looking into ‘the standard agreements between Amazon and marketplace sellers, which allow Amazon’s retail business to analyse and use third party seller data’ (see my discussion here).

On the other side of the Atlantic, Facebook is facing scrutiny. In announcing its 2019 Q2 results, the social network reported that ‘we were informed by the FTC [Federal Trade Commission] that it had opened an antitrust investigation of our company’. The focus of the investigation is not clear yet, but Facebook’s copying of competitors is rumoured to be one of the practices that the FTC is looking into. And Amazon is not off the hook either: in recent Congressional antitrust hearings, it faced questions on how it identifies the most popular products on its marketplace and copies them.

To find the antitrust angle in these investigations, however, it is necessary to separate three different yet related dynamics. Firstly, a company can copy a competitor’s product. Secondly, a company can copy a competitor’s product using data it has access to in its role as vertically integrated platform operator distributing that competitor’s product. Thirdly, the platform can use that ‘dual role’—as both platform/distributor and retailer/competitor—to give its own products a leg up in distribution, e.g. by giving it more prominent placement on its platform. Complainants thus have to start by figuring out which situation they find themselves in, because if there is an antitrust problem, it’s situated in the latter two scenarios.

Copying a competitor

Simply copying a competitor is not an antitrust problem. It could present an issue of intellectual property. Note, for example, how Amazon isn’t the first company to copy Allbirds. In December 2017, the sneaker company brought a claim against Steve Madden for having ‘copied Allbirds’s Wool Runner Trade Dress in an effort to exploit Allbirds’s reputation in the market’ (see image below). The claim thus relied on an infringement of trade dress, which requires that the product carries a ‘secondary meaning’, e.g. through exposure and advertising. The case was eventually settled, but other cases are still ongoing.

However, these cases rely on intellectual property rights (and related claims of unfair competition), not antitrust law—and rightly so. If Allbirds decides to bring a case, it will have to advance these kinds of claims against Amazon. Indeed, a search on Amazon.com for ‘Allbirds’ leads to a wide variety of lookalikes (see image below), but no sneakers offered by Allbirds itself. Therefore, data on sales of Allbids sales cannot have prompted Amazon to come up with its version of wool sneakers. At most, Amazon may have noticed that searches for ‘wool sneakers’ were on the rise. Finally, let’s not forget that (legal) copying is ‘rampant’/happens ‘all the time’ in fashion. The fact that intellectual property rights appear relatively weak in this area can reflect a choice by the legislator—a choice that antitrust law shouldn’t be too quick to frustrate.

Copying a competitor—and using your platform for inspiration/promotion

What if one firm doesn’t just copy a competitor but (i) does so based on data it has access to in its role as vertically integrated platform operator distributing that competitor’s product; and/or (ii) uses that ‘dual role’—as both platform operator and retailer—to give its own products a leg up in distribution, e.g. by giving it more prominent placement on its platform? Then the situation more complex. One could argue this constitutes an instance of leveraging: the platform uses its dominant position in one market (the platform market) to gain a foothold in an adjacent market (the retail market). Under certain circumstances, such leveraging can exceed competition on the merits and be illegal.

Of course, the copying would have to result in anticompetitive effects. One could argue that copying results in a decrease in innovation: if platform operators (systematically) appropriate the investments of the users active on their platform (in this case, retailers), the users’ incentive to come up with new products or to improve existing products decreases. Legal scholars have discussed such conduct as ‘forced free-riding’ or ‘predatory copying’ (see also the discussion in this OECD background note). But note that this theory of harm doesn’t fully apply when the copied product wasn’t available on the platform in the first place (which goes not only for Amazon/Allbirds, but also for Facebook/Snapchat).

Of course, there are also strong counterarguments against a (successful) antitrust case based on the copying by platforms of products within their ecosystem. For one, supermarkets and other retailers have been producing their own private label products for years, and have given them prominent placement on their shelves. While the potential anticompetitive effects of such conduct have been discussed (see e.g. here), it has—to my knowledge—not led to major antitrust decisions. Additionally, as Annemarie Bridy reminds us, ‘copying generally results in lower prices that benefit consumers’.

The inquiry may thus turn on the relative strength of the various effects of the conduct in question, by which I mean not only the magnitude of each effect, but also the value we assign to it. When it comes to Amazon’s entry into the product spaces of third-party sellers, the question thus becomes: do we give more weight to price or innovation effects, and how strong are they in this case? Data to help us answer this question is still scant, although Zhu and Liu have conducted a helpful empirical study, in which they find that ‘Amazon’s entry discourages affected third-party sellers from subsequently pursuing growth on the platform, [but] increases product demand and reduces shipping costs for consumers.’

Conclusion

Simply copying a competitor can hardly be called an antitrust problem—often, it will not even pose an issue of intellectual property (although I’m no expert on that subject). In this sense, and notwithstanding how much I love my own pair of wool sneakers, picking Amazon/Allbirds as a poster child for what’s wrong with Silicon Valley is a questionable choice (all the more so because Amazon is headquartered in Seattle, but that location just doesn’t have the same ring to it).

When online platforms copy products by relying on their unique position as platform operator, there might be an antitrust issue. In that case, however, it is not so much the copying that is problematic; rather, it is the (ab)use of the platform’s privileged position or ‘dual role’ as both platform operator and retailer. Of course, this conduct only comes under the scope antitrust law (at least its abuse of dominance/monopolization provisions) when the platform has market power. And even then, work remains to be done to tease out how exactly copying by platforms is competitively different from its offline equivalent (e.g. by supermarkets, which similarly fulfil a dual role). Does the platform’s superior access to data on third-party transactions make the difference? And/or is it the unique way in which platforms can use their search algorithms and online interface to steer consumers towards their own products?

To be continued.