Economies of scale do not necessarily correlate with ability to pay.

Introduction

On Thursday, 11 July 2019, France became the first European country to adopt a tax on digital sales. At about the same time, President Donald Trump warned that the US would retaliate with punitive tariffs. The US believes that the tax is aimed at its internet giants such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Indeed, the structure of the French tax does fuel American suspicion that the tax targets US companies. The rate of the tax is a mere 3%. But it applies only to companies with annual global sales of more than €750 million and French sales exceeding €25 million. Probably the Chinese Alibaba is also caught by the tax, but not many other companies.

For the purposes of this article the question is not whether those companies deserve to be taxed [they do], whether the tax will be effective [possibly] or whether there should be a coordinated global approach [definitely]. Rather, it is whether the French tax infringes Article 107(1) TFEU. Given that the threshold for the application of the tax is very high, is it just a tax on large companies in disguise?

If it ever needs to defend its measure before EU courts, France will surely rely on two very recent judgments of the General Court, which indicate that taxing the size of sales is not a hidden form of State aid to small companies. On 16 May 2019, in case T-836/16, Poland v European Commission and on 27 June 2019, in case T-20/17, Hungary v European Commission, the General Court, relying on largely identical reasoning, ruled that turnover taxes with multiple rates and bands did not constitute State aid.

Consequently, the General Court also annulled the related Commission decisions which had concluded that the Polish and Hungarian measures granted incompatible State aid to companies with turnover below certain thresholds, which were subject to lower tax rates.

The judgment on the Polish measure was reviewed here on 18 June 2019 (view blog post here: http://stateaidhub.eu/blogs/stateaiduncovered/post/9523).

The judgment on the Hungarian measure is very similar and does not really add any new point of law.[1]

I ended the article of 18 June 2019 by asking whether the judgment on the Polish retail tax would embolden Member States “to tax company size and target large retailers such as Amazon”. I did not know at that time that three weeks later the French senate would approve the digital tax. Nor, do I know whether the decision of the French senate was influenced by the Polish and Hungarian legal victories. But given these developments, it is worth revisiting these two judgments and examine more carefully the reasoning of the General Court on the taxation of turnover above a certain threshold.

There is another reason for revisiting these cases. Unlike the judgment on the Polish measure, the judgment on the Hungarian measure is available in English too. This means we can have a more precise understanding of the central premise in the Court’s syllogism.

Ability to pay

Poland and Hungary successfully pleaded in their respective cases that the different rates and bands of their taxes were integral components of the reference system and that the Commission was wrong to identify deviations from a hypothetical reference rate. They also persuaded the General Court that the progressive rates [i.e. higher rates levied on turnover above certain thresholds or in certain bands] were designed to gradually raise the burden of the tax as companies generated more turnover. In other words, the tax was intended to correspond to taxpayers’ increasing ability to pay.

The Commission considered that a turnover tax could not be progressive and had to be based on a single rate. The Commission relied on the judgment of the Court of Justice in case C-106/09 P, European Commission v Gibraltar, to argue that the tax was expressly designed to favour small companies or, to be more precise, companies with low turnover.

In the Polish and Hungarian cases, the General Court accepted that the progressive rate of tax corresponded to ability to pay because as companies grew and generated more revenue they also reaped savings from economies of scale which meant that they had more “disposable” revenue that could be taxed. The Court developed this argument in just one paragraph.

To be able to compare the relevant paragraphs from the two judgments, their text in French is quoted below.

This is the relevant paragraph from the judgment on the Polish measure. “(75) Par ailleurs, contrairement à ce que soutient la Commission, l’économie de l’impôt en cause, caractérisée par une structure d’imposition progressive, était a priori cohérente avec cet objectif même si l’impôt en cause était un impôt sur le chiffre d’affaires. En effet, il est raisonnable de présumer que l’entreprise qui réalise un chiffre d’affaires élevé peut, grâce à différentes économies d’échelle, avoir des coûts proportionnellement moindres que celle qui réalise un chiffre d’affaires plus modeste – parce que les coûts unitaires fixes (bâtiments, impôts fonciers, matériel, frais de personnel par exemple) et les coûts unitaires variables (approvisionnements en matières premières par exemple) diminuent avec le volume d’activité – et qu’elle peut jouir ainsi d’un revenu disponible proportionnellement plus important qui la rend apte à payer proportionnellement plus au titre d’un impôt sur le chiffre d’affaires.”

This is the relevant paragraph from the judgment on the Hungarian measure. “(89) Toutefois, contrairement à ce que soutient la Commission, l’économie de la taxe sur la publicité, caractérisée par une structure d’imposition progressive, était a priori cohérente avec l’objectif des autorités hongroises, même si l’impôt en cause était un impôt sur le chiffre d’affaires. En effet, il est raisonnable de présumer que l’entreprise qui réalise un chiffre d’affaires élevé peut, grâce à différentes économies d’échelle, avoir des coûts proportionnellement moindres que celle qui réalise un chiffre d’affaires plus modeste – parce que les coûts unitaires fixes (bâtiments, impôts fonciers, matériel, frais de personnel par exemple) et les coûts unitaires variables (approvisionnements en matières premières par exemple) diminuent avec le volume d’activité – et qu’elle peut jouir ainsi d’un revenu disponible proportionnellement plus important qui la rend apte à payer proportionnellement plus au titre d’un impôt sur le chiffre d’affaires.”

Since the Hungarian judgment also exists in English, this is the Court’s English translation of the same paragraph. “(89) However, contrary to the Commission’s submissions, the scheme of the advertisement tax, characterised by a progressive tax structure, was a priori consistent with the Hungarian authorities’ objective, even though the tax at issue was a turnover tax. It may reasonably be presumed that an undertaking which achieves a high turnover may, because of various economies of scale, have proportionately lower costs than an undertaking with a smaller turnover — because fixed unit costs (buildings, property taxes, plant, staff costs for example) and variable unit costs (raw material supplies for example) decrease with levels of activity — and that it may, therefore, have proportionately greater disposable revenue which makes it capable of paying proportionately more in terms of turnover tax.”

I will argue that this paragraph contains three errors: an error of logic, an economic error, and a legal error.

The logical error: What the General Court calls “disposable revenue” is simply profit which is the difference between revenue and costs. In order to justify the progressivity of the turnover tax, the General Court merely says that those companies that generate more profit as a result of economies of scale can afford to pay more taxes. This reasoning does not prove that higher turnover leads to increased ability to pay. It only justifies the progressivity of profit taxes.

The economic error: Any company may experience economies of scale as it grows, but it does not necessarily follow that two different companies that reach the same turnover have the same “disposable revenue” and therefore the same ability to pay. This is because the rate of the reduction in average costs may vary across companies. To put it differently, there is no reason to expect that economies of scale are similar across companies, even for companies in the same sector. The next section demonstrates this with a numerical example.

The legal error: Since any two companies with the same turnover may not have the same cost structure, a progressive turnover tax, which is based on the presumption that companies with the same turnover have the same ability to pay because they have the same “disposable revenue”, in fact treats in the same way companies that are in a dissimilar situation. This is another form of discrimination. Therefore, a progressive turnover tax favours companies that experience a steeper reduction in their average cost or, conversely, penalises companies that experience a lower reduction in their average cost. Moreover, according to the three-step test of selectivity in the case law, there is nothing intrinsic in a turnover tax that can justify modulation of the tax according to costs.

The next two sections use numerical examples to demonstrate, first, that larger turnover does not necessarily mean more “disposable revenue”. Second, companies with the same turnover may in fact be treated unequally because companies with the same turnover may not have the same ability to pay. And, third, the argument of economies of scale is not valid in all situations because even if companies reap the benefits from economies of scale as they grow, they may still not achieve the same ability to pay.

Do you know we also publish a journal on State aid?

The European State Aid Law Quarterly is available online and in print, and our subscribers benefit from a reduced price for our events.

Example 1: Larger turnover does not mean increased ability to pay

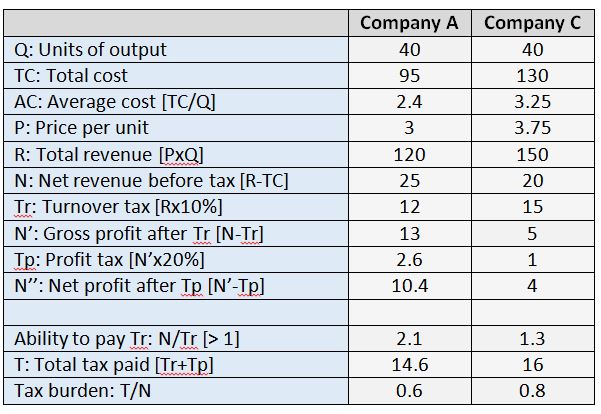

Assume that there are two companies, A and C, with costs and revenue as indicated in table 1 below. The turnover tax is 10% while the profit tax is 20%. I assume that the profit tax is levied on net profit after the turnover tax is paid. For simplicity, I also assume that the turnover tax has only one rate and one band [these assumptions make it harder to prove my argument].

In both examples companies are made to be as similar as possible. Yet the results can be surprising.

In this and the following example ability to pay is defined as the ratio of net revenue before turnover tax, N, over the amount of the turnover tax, Tr. For a company to be able to pay the tax, the ratio N/Tr must exceed 1. The higher the number, the higher the ability to pay.

Table 1

Company C has a larger turnover because it charges more for its product because it is of higher quality. For this reason, its costs are also higher than those of company A.

Company C has a larger gross revenue than A, but smaller net revenue than A because A’s costs as lower. Although company C has a lower ability to pay, it ends up paying a larger amount of turnover tax and a larger total amount of tax [i.e. turnover and profit tax]. Company C also bears a larger tax burden in proportion to its net revenue.

Therefore, the general statement that a company can afford to pay more simply because it has a larger turnover is not valid. The presence of economies of scale may enable a company to earn more as it grows, but it cannot be used to make any meaningful comparison between companies.

Example 2: Economies of scale and unequal ability to pay

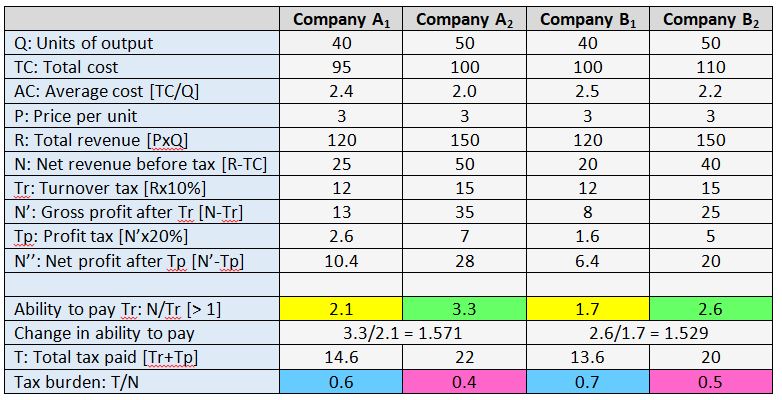

Let there be two companies, A and B. Subscript “1” indicates a lower turnover and subscript “2” indicates a higher turnover with lower average cost, i.e. with economies of scale. Since the purpose of this section is to show that the presence of economies of scale does not necessarily mean that companies with the same turnover have the same ability to pay, it is sufficient that the tax has a single rate and a single band. The two companies are presumed to start from identical turnover and achieve the same level of turnover as they grow. They are identical except in their cost structure.

Table 2

The results which are derived are counterintuitive. Both companies pay 12 in turnover tax when their output is 40 and 15 when their output is 50. Yet their ability to pay varies in both output situations. Compare the yellow cells, corresponding to output of 40, and the green cells that correspond to output of 50. Two companies with the same output and which charge the same price, therefore, earning the same turnover, end up with different “disposable revenue”. This is the result of their different costs.

Because of economies of scale, as the two companies grow their ability to pay increases. But the row below the yellow and green cells shows that that ability increases at a different rate even though they reach the same turnover and pay the same turnover tax.

These two results are sufficient to demonstrate that the presence of economies of scale does not necessarily mean that companies with the same turnover or companies that reach the same turnover have the same ability to pay. I hasten to add that the example does not prove that this is the case in all possible situations. It only shows that a general statement, like that made by the General Court, does not hold. Therefore, a turnover tax, and especially a progressive turnover tax with rising rates, treats in the same way companies which are not in a similar situation in terms of their ability to pay.

Finally, it is worth noting that a turnover tax combined with a normal profit tax can result in a perverse situation whereby the company with the higher ability to pay [i.e. company A] bears a lower overall tax burden, defined as the ratio of total tax, T, over net revenue, N. Just compare the blue cells and the purple cells.

Turnover taxes only accidentally correlate with ability to pay as companies grow in size.

What are the implications for digital taxes?

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, France has already imposed a digital tax which very much resembles a turnover tax. It has a single rate, but a very high threshold. The Commission does not object to single-rate turnover taxes. But could the high threshold be construed as State aid to companies with lower turnover? Perhaps.

The Commission has already lodged its appeal against the judgment of the General Court on the Polish tax [C-562/19 P, Commission v Poland]. We will have to wait to see what the Court of Justice will make of the argument that economies of scale justify progressive turnover taxes with multiple rates and/or multiple bands.

As always is the case with fiscal aid, the critical issue is whether digital taxes treat differently companies which are in a similar legal or factual situation. Perhaps it may be possible to argue that the taxation of internet-based sales of non-resident companies is not selective because they are not in the same situation as companies which are resident for tax purposes and that the tax on digital sales is intended to offset partly their avoidance of profit tax.

—————————————

[1] The full text of the judgment can be accessed at: